|

Updated: 2019.10.30 ![]()

|

The enigma of Shi•mᵊsh•ōnꞋ![]() slaying 1,000 Pᵊli•shᵊt•inꞋ with a “jawbone of an ass” has baffled every rabbi, commentator and interpreter from time immemorial—until now.

slaying 1,000 Pᵊli•shᵊt•inꞋ with a “jawbone of an ass” has baffled every rabbi, commentator and interpreter from time immemorial—until now.

When I searched the web for how a jawbone from an ass might be used as a weapon, it was simply unwieldy. Additionally, a “fresh” jawbone (15.15) would be messy and slippery with blood. Beyond that, in the scene where Shi•mᵊsh•ōnꞋ![]() breaks off his ropes while standing between 1,000 Pᵊli•shᵊt•inꞋ and his own 3,000 Yᵊhud•imꞋ, why would a freshly-killed donkey be within reach? And why would the Pᵊli•shᵊt•inꞋ simply stand around and watch Shi•mᵊsh•ōnꞋ

breaks off his ropes while standing between 1,000 Pᵊli•shᵊt•inꞋ and his own 3,000 Yᵊhud•imꞋ, why would a freshly-killed donkey be within reach? And why would the Pᵊli•shᵊt•inꞋ simply stand around and watch Shi•mᵊsh•ōnꞋ![]() remove the head from the donkey, clean its skull and remove its jawbone for a weapon?

remove the head from the donkey, clean its skull and remove its jawbone for a weapon?

Over decades, I’ve found that reality, science and logic always explain the “supernatural miracles” that cause so many to dismiss Ta•na"khꞋ stories as silly fairytales. The story of Shi•mᵊsh•ōnꞋ![]() and the jawbone of an ass turns out to be no exception.

and the jawbone of an ass turns out to be no exception.

Growing up watching Old West cowboy TV shows, I remember Festus and Gabby Hayes types referring to the famous 1873 Colt .45 six-gun revolver as a “hogleg”.

A prior, this had to be a colorful and metaphorical descriptive and—instantly—the “hogleg” six-gun came to mind. Was there an ancient weapon that resembled the jawbone of an ass enough to inspire it to be called by that name? In 1972, A.A. Barb had traced similar metaphorical usage of animal body parts to sickle-like weapons of the Biblical era—including a “jawbone of a camel”; and one of his photos vaguely resembled a jawbone.

|

| Type II Sickle Sword, c. BCE 1900-1700 |

|

| Jawbone of an ass; either side resembling a weapon. |

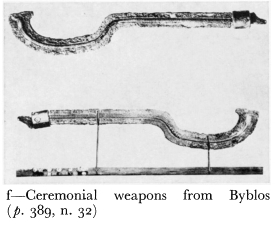

Barb includes, among a number of other sword type depictions, a photograph of a Khopesh-type ceremonial “sickle” from Byblos (photo f).

”[T]here might have existed an old popular name for the sickle which meant verbally just such a jawbone. There have always been in use in all languages similar picturesque animal names for tools, like ‘ram’, ‘crane’, ‘monkey-wrench’, ‘rat-tail’ (for a thin round file [or comb with a thin round handle, ybd] in English… and the Babylonian name gamlu for the sickle-weapon of Marduk has been explained etymologically as ‘jawbone of a camel’.”![]()

|

| Reproduction of Bronze Age LᵊkhiꞋ-Kha•mōrꞋ (”Jawbone Of An Ass”) “úÅÌì àÂôÅ÷ Khopesh Sword” |

”The Khopesh, also known as the sickle-sword, is a curved, single edged sword from the Near East, mainly Egypt and Canaan. The Egyptian term "khepesh", hinted at the resemblance to the foreleg of a cow or an ox, as well as it was its owner's "mighty arm".

”The khopesh first appeared in the Middle Bronze Age, in the centuries before 2000 B.C., and went out of use after 1200 B.C. For the Middle Bronze Age specimens, the typology established by H.W. Müller (1986) seems still sound (groups I, II and III).”![]()

The spur, or hook, on the outside curve of the weapon was used to hook the enemy’s shield and, in one continuous quick motion, pull it out of the way in order to push the outside of the curved blade in the enemies now-unprotected neck. While some ìÀçÄé-çÂîåÉø swords were sharpened only on the outside curve of the blade, others have been found sharpened only on the inside curve of the blade. Ceremonial swords aside, doubtless, battle swords were sharpened on both edges.

Transliterating the Egyptian “Khopesh” into Hebrew, the ç'åôù (or ç'ôù) thereby came to mean “The Peacemaker” (lit. “The Freedom”).

The text reads ìÀçÄé-çÂîåÉø èÀøÄéÌÈä — a freshly-forged ìÀçÄé-çÂîåÉø sword. He didn’t jump any old sword. He jumped a freshly-forged, new weapon in mint shape, fit for battle.

The text doesn’t read that he “reached down” or simply “picked it up” from a dead donkey on the ground. Rather, the text reads åÇéÌÄùÑÀìÇç éÈãåÒ åÇéÌÄ÷ÌÈçÆäÈ. While this could refer to “taking” a “fresh jawbone of an ass”, there is no mention of him cleaning off the flesh, tough hide and hair, or the weapon being slippery because of the “fresh” blood. However, it makes more sense to refer to finding a Pᵊli•shᵊt•inꞋ with a shiny, new, freshly-forged sword and, like “jumping his gun” today, Shi•mᵊsh•ōnꞋ![]() “jumped his sword”.

“jumped his sword”.

Throughout history, historians have credited battle victories, along with the slain, to the general or king. Dâ•widꞋ ha-MëlꞋëkh alone provides a number of such examples. Thus, instead of ascribing supernatural foreign hero-god status to Shi•mᵊsh•ōnꞋ![]() , we should read the text like all of the other examples: Shi•mᵊsh•ōnꞋ

, we should read the text like all of the other examples: Shi•mᵊsh•ōnꞋ![]() mustered an army that, armed áÌÄìÀçÄé-äÇçÂîåÉø, çÂîåÉø çÂîÉøÈúÈéÄí; áÌÄìÀçÄé-äÇçÂîåÉø, he attacked 1,000 Pᵊli•shᵊt•inꞋ.

mustered an army that, armed áÌÄìÀçÄé-äÇçÂîåÉø, çÂîåÉø çÂîÉøÈúÈéÄí; áÌÄìÀçÄé-äÇçÂîåÉø, he attacked 1,000 Pᵊli•shᵊt•inꞋ.

|

|