Parashat wâ-Yei•râꞋ (vayera) -

Teimani Weekly Torah (Netzarim Israel)

| Torâh | Haphtârâh | Âmar Ribi Yᵊhoshua | Mᵊnorat ha-Maor |

|---|---|---|---|

5776 (2015.11)

The Real òÂ÷ÅãÈä

So Avᵊrâ•hâmꞋ loaded his caravan pack-animals and wrapped a cloth saddle on his donkey. Confident that he could trap the needed sacrifice tzon in the mountainous wilderness of Mo•riy•âhꞋ,22 he took two of his young ranch hands and his son, Yi•tzᵊkhâqꞋ, with him – likely opting not to lead a sacrifice animal on the long journey when he could snare an appropriate sacrifice animal on site. He split wood for the ascendance, then got up and went to the place ha-Ël•oh•imꞋ had told him.

Snares that entangle horns or antlers are probably illegal nowdays. That's probably why I haven't been able to find a diagram or photo to illustrate. Using a bit of grain for bait, such a trap in Biblical times and, the destination being nearby a wildernous mountainous area known for game, would have been highly effective and regarded as reliable. Though the text recounts that Avᵊrâ•hâmꞋ carried (sacred) fire for the sacrifice, he saw no need to lead a sacrifice animal throughout the whole journey when he expected to easily and quickly snare an appropriate sacrifice animal in the mountainous wilderness nearby the destination site.

The last-second appearance of the aꞋyil suggests that there was a time deadline associated with the sacrifice. Avᵊrâ•hâmꞋ chronologically antedated the origins of all three Khaj•imꞋ. A priori, the likely deadline was either Yom Tᵊru•âhꞋ of Yom ha-Ki•pur•imꞋ.

As the deadline approached and Avᵊrâ•hâmꞋ had failed to snare an appropriate sacrifice animal, he deduced that é‑‑ä was requiring him to sacrifice his son, and he was being obedient. But, then, at the last moment, he perceived a warning from é‑‑ä. After that, Avᵊrâ•hâmꞋ decided to make another final check of the snares he had set and, behold, an aꞋyil ðÆàÂçÇæ áÌÇñÌÀáÇêÀ which he interpreted as é‑‑ä having provided the aꞋyil for the ōl•âhꞋ.

|

5772 (2011.12)

My òÂ÷ÅãÈä Moment

|

I'm writing this as my own A•qeid•âhꞋ moment has just occurred during this KhaꞋnukh•âh of 2011.12. For the past several months, a conflict has been brewing between the majority of Israelis, who are moderate, against the Ultra-Orthodox khareid•imꞋ.

For the past year, since my daughter has developed a serious relationship with the potential for marriage, I've felt pressure (from the situation, not from my daughter) to restrain my keyboard relative to criticizing the Ultra-Orthodox khareid•imꞋ, who control the Ra•bân•utꞋ, who, in turn, control whether our conversions – by an Orthodox Rabbi and confirmed by Sha"s when we made a•liy•âhꞋ in 1985 – will be upheld and, accordingly, whether they will grant her registration to marry here in Israel.

This past week, with the boiling-over of tensions exemplified by a globally reported protest against the Ultra-Orthodox khareid•imꞋ in Beit ShëmꞋësh, the conundrum struck me: I'm being forced to choose between sacrificing Tor•âhꞋ and the well-being of Yi•sᵊ•râ•eilꞋ (by suspending my opposition to the abuses of Tor•âhꞋ and the resulting khi•lulꞋ é--ä by the Ultra-Orthodox khareid•imꞋ) on the one hand, or risk the ire of the Ultra-Orthodox khareid•imꞋ, thereby increasing the likelihood that I'm sacrificing my daughter's likely prospects to obtain permission from the Israeli Ra•bân•utꞋ to marry – not to mention our own (my wife and I) prospects. We're all three being sacrificed on the same, Ultra-Orthodox (Costume Jewry) / Kha•

This was my A•qeid•âhꞋ moment: sacrifice Tor•âhꞋ and the well-being of Yi•sᵊ•râ•eilꞋ – or sacrifice the well-being of my daughter. So, I placed my daughter in the hands of é--ä, and immediately resumed criticizing the strayings, apostasies and heresies against Tor•âhꞋ by the Ultra-Orthodox khareid•imꞋ. Time will disclose whether my daughter is delivered and able to marry under the auspices of the Ra•bân•utꞋ or, when the time comes, é--ä has better plans for her and she is forced to make other arrangements. My decision, and sacrifice, has been made, carried out and will continue. Just as Av•râ•

When I realized the parallel with the A•qeid•âhꞋ, I realized that there's a lot we don't know about Av•râ•hâmꞋ's A•qeid•âhꞋ moment; about what pressured Av•râ•hâmꞋ to feel that he had to sacrifice his son? And for what purpose? What was the objective he was sacrificing to achieve? Perhaps, these details were omitted so that others could experience their own A•qeid•âhꞋ moment?

|

Early 2012 Update: We have hired Israeli attorneys to fight the Rabbinate's "sudden no longer recognizing" our 1984 American Orthodox conversions – after more than 25 years living as Orthodox Jews in Israel and with an Israeli born-Jew daughter having never known anything else. So far, we've already spent over ₪17,000 (roughly US $4,500) on legal expenses.

Late 2012 update:

The Costume Jewry (Ultra-Orthodox) Chief Torah-tweakers (Rabbinate) are between a rock and a hard place: They cannot prove truth false: that the two Orthodox rabbis (a third witness was an upstanding male Jew) who supervised our conversions were not Orthodox rabbis, any more than they can prove that the moon doesn't exist.

On the other hand, they are dead set against "recognizing" followers of Jesus and leave Christianity – as Christian!

That is their dilemma. They recognize that they can win neither case outside of their own, Ultra-Orthodox kangaroo bât•ei

For nearly 50 years, I've brought my research to the public, for the benefit of Christians, Muslims and Jews who have been misled about 1st century C.E. history, without seeking financial help. But this is a pushback from fanatics who happen to control the Rabbinate, at odds with both moderate Orthodox Jews around the world as well as secular Israeli Jews, but who enjoy enormous financial and political backing. We need all of the financial help (please label these contributions "legal fund") from anyone who can help. Donors can inquire via our Web Café. (Neither inquiries concerning the legal fund nor donations will be posted in the Web Café. So donors will remain anonymous. The Web Café is just the simplest and easiest means of handling inquiries and communications without resorting to announcing email addresses to spammers.)

"One who gives even a single vessel of cold water 10.42.1 to one of my little tal•mid•

imꞋ , for the name 10.41.1 of a tal•midꞋ of mine – â•meinꞋ ! – I tell you, in no case shall his payments be lost." (The Nᵊtzârim Reconstruction of Hebrew Matitᵊyâhu (NHM, in English)10.42 with notes 10.41.1 & 10.42.1)

|

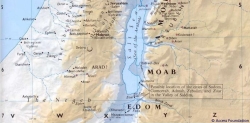

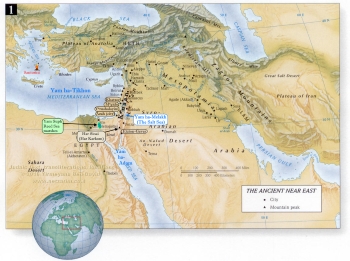

| Setting: ca. B.C.E. 2087. Location: Ei•lon•eiꞋ MamᵊreiꞋ (31° 33' N, 35° 6' E; see map below) |

Yi•rᵊmᵊyâhꞋu, QërꞋën and Yâ•eilꞋ at the Me•âr•atꞋ ha-Makh•peil•âhꞋ (1996), near Ei•lon•eiꞋ MamᵊreiꞋ. |

|

5770 (2009.11)

Does é--ä Eat Khâ•lâvꞋ with Bâ•sârꞋ?(bᵊ-Reish•itꞋ 18.8)

é--ä is not physical, and a non-dimensional Singularity does not feed on physical substances of any kind. Anthropomorphism is a contra-Judaic belief that has never been acceptable in Tor•âhꞋ. Thus, there are several aspects of the account in bᵊ-Reish•itꞋ 18 that—like all of Tor•âhꞋ—must be understood Judaically rather than idolatrously.

Most of these points have been discussed in previous years (below). I've been skipping over 18.8 because I was sure I had already covered it and I didn't want to be repetitive for those who read through the commentary over the years. When asked, recently, to explain Av•râ•hâmꞋ serving khâ•lâvꞋ and bâ•sârꞋ to é--ä, however, I looked for a quotation in this pâ•râsh•âhꞋ to save time (and hint that he should have read the pâ•râsh•âhꞋ), I discovered I hadn't covered it here. (Perhaps I covered it in the newsletter archive topics.) So, relying on aspects that I have covered in previous years (one should always begin reading the pâ•râsh•âhꞋ starting with the earliest year and reading in reverse chronological order) the answer follows below.

The rabbis have answered two aspects of this question satisfactorily.

- Tor•âhꞋ had not yet been given and, therefore, was not incumbent upon Av•râ•hâmꞋ any more than it had been upon NoꞋakh or •dâmꞋ and Khaw•âhꞋ. Tor•âhꞋ developed continuously from the time of •dâmꞋ and Khaw•âhꞋ not only until Mosh•ëhꞋ at Har Sin•aiꞋ, but, while Tor•âhꞋ shë-bi•khᵊtâvꞋ cannot be modified, Tor•âhꞋ shë-be•alꞋ pëh (Ha•lâkh•âhꞋ) continues to develop, to interpret the intent of Tor•âhꞋ shë-bi•khᵊtâvꞋ in the dynamic world of changes and advances—today and on into the future.

- What is the rule of logic? In all cases, including all interpretations of the Bible, the known is assumed and it is the deviation from the known that must be proven; never the reverse. In this case, we know that Yi•sᵊr•â•eilꞋ has separated khâ•lâvꞋ from bâ•sârꞋ as far back as there is documentation; with no evidence to the contrary. "Might be interpreted" contrary to this known (in harmony with Hellenism instead) is a contradiction of logic, not evidence or proof. If there is no certain evidence or proof to the contrary, separation of khâ•lâvꞋ from bâ•sârꞋ remains uncontradicted. In other words, separation of khâ•lâvꞋ from bâ•sârꞋ, not a Christian or other contra-Tor•âhꞋ perspective, is assumed until proven otherwise.

Notice that Av•râ•hâmꞋ sent "the youth" off to slaughter and butcher, then roast, the calf. How long does that take? Would Av•râ•hâmꞋ keep his important guests waiting for so long without serving them something to tide them over? What time of day was it when these distinguished guests arrived? "The heat of the day," midday. Which sounds most sane to serve under a tree by a tent in the worst, midday heat of the raw, blazing midday sun of the middle east—hot roast calf or cool dairy foods?

And what time did the guests leave? Because the account states that the men "came to Sᵊdom (a couple of km south of the southern tip of Yâm ha-MëlꞋakh) in the evening," (19.1), some have made the ludicrous assertion that these men must have left after lunch… to walk the distance of 55 km (more than 34 miles) before evening! When "angels" can leap 55 km in a single bound, then Muhammed's horse can fly into the heavens. Certainly, the trip took more than one day and provides no indication what time of day, or even which day, these men departed from Av•râ•hâmꞋ's tent.

There was likely much conversation and discussion in the intervening period between the serving of khâ•lâvꞋ and the later serving of bâ•sârꞋ—probably in the evening around the fire in front of the tent, as was the practice in the mideast as, despite the blazing heat of the day, evenings in the hills of Khë•vᵊr•onꞋ are surprisingly chilly… and conducive to a convivial hot meal of roast veal.

Notice, too, that Khâ•lâvꞋ is mentioned before bâ•sârꞋ. This is a further suggestion that the khâ•lâvꞋ was served first.

This ancient middle-east custom of serving a light, cool dairy lunch and having meat only in the evening for special occasions (including Shab•âtꞋ) continues among òÅãåÉú äÇîÄÌæÀøÇç in Israel and neighboring Arab countries.

This is not only compatible with Ha•lâkh•âhꞋ at Har Sin•aiꞋ (and today, of course), but certainly was the paradigm upon which the present Ha•lâkh•âhꞋ was predicated as Tor•âhꞋ continued to develop.

The above was answered well long ago by the rabbis. What the rabbis still haven't realized, however, is that there is yet another aspect that further collaborates their conclusion. The separation of khâ•lâvꞋ from bâ•sârꞋ is first documented at Har Sin•aiꞋ, after the Yᵊtzi•âhꞋ.

Most people haven't read the account closely and remain unaware that many goy•imꞋ—"åâí òøá øá" (Shᵊm•otꞋ 12.38)—threw their lot in with Yi•sᵊr•â•eilꞋ and left Egypt, along with Yi•sᵊr•â•eilꞋ, in the Yᵊtzi•âhꞋ. It was only after this first, large scale, incorporation of geir•imꞋ that it became necessary to emphasize, to both geir•imꞋ and Yi•sᵊr•â•eil•imꞋ the requirement of

- geir•imꞋ—spiritual kids in Tor•âhꞋ—being weaned from their mother country's culture, which had been the milk on which they had been raised and

- prohibit Yi•sᵊr•â•eilꞋ from persecuting the geir•imꞋ, who had left everything, by slandering (boiling) them as goy•imꞋ (in their mother's milk)

Since this was likely instituted as a consequence of the mass infusion of geir•imꞋ in the wake of the Yᵊtzi•âhꞋ (and subsequent mass absorptions under Yᵊho•shuꞋa Bin-Nun), this may not have been Ha•lâkh•âhꞋ in the time of Av•râ•hâmꞋ.

|

5767 (2006.11)

To minimize the enormous bandwidth consumed by video data (disk space, dictating loading time), as much content as possible is diverted to the text section (below), with the video handling only the parts that cannot be handled as well by text alone. For this reason, videos are archived in YouTube. Ta•na"khꞋ selections are read from the SeiphꞋër Tor•âhꞋ ha-Tei•mân•iꞋ, the ëÆÌúÆø àÂøÈí öåÉáÈà (Aleppo Codex), an Artscroll Ta•na"khꞋ or iQIsa, as appropriate, and pronounced according to No•sakhꞋ Tei•mân•itꞋ.

Note: YouTube, upon being acquired by Google, deleted our account and our videos – leaving a host of phonies calling themselves "Netzarim."

Isolated and Alone in an Evil Environment

Don't make Lot's mistake

Every Christian, or assimilated Jew, who lives geographically distant from the Tor•âhꞋ Jewish community begins to see, as he or she learns to live according to Tor•âhꞋ, the sharpening contrast against their native—goy•imꞋ—environment, which is antinomian (anti-Tor•âhꞋ) and contrary to é--ä; an evil environment oriented around individual hedonism, focused solely on greed and the pursuit of prosperity. Turning to learn and keep Tor•âhꞋ entails building a Havdâl•âhꞋ (separation) between yourself and the surrounding goy•imꞋ environment.

Having abandoned Christianity, but not yet having learned to keep Tor•âhꞋ to the point of integrating into a Tor•âhꞋ Jewish community, the former Christian, and sometimes even an estranged Jew, finds himself or herself between communities, in limbo; no longer enjoying fellowship with Christians and goy•imꞋ, but not yet able to develop fellowship with the Tor•âhꞋ Jewish community. Consequently, during this transition you will find yourself alone; in extreme isolation, feeling a near-paralyzing feeling of aloneness. People around you usually don't come out and tell you that "Judaism" is wrong. Rather, they tell you that you are wrong; all by yourself—alone. People around you usually don't come out and tell you that "Judaism" is a cult. Rather, they tell you that you are following a cult; all by yourself—alone.

Assimilated Jews desiring to return to Tor•âhꞋ are frequently alien to Tor•âhꞋ and the Tor•âhꞋ community, living in a goy•imꞋ environment that they, likewise, suddenly discover is antinomian (anti-Tor•âhꞋ), which they had never noticed or realized before, and contrary to é--ä; an evil environment oriented around individual hedonism, focused solely on greed and the pursuit of prosperity. Embarrassed to admit that they don't know what every Jew is supposed to know, the estranged Jew, too, often remains isolated and alone rather than expose their ignorance in order to accept instruction.

Thus, as RibꞋi Yᵊho•shuꞋa observed, the path to Tor•âhꞋ is, indeed, lonely, isolated, narrow, steep and difficult; a path of isolation, aloneness and rejection by "everybody" in the alien goy•imꞋ environment of individual hedonism, focused solely on "me" and materialism.

To remain in this limbo long is a sure recipe for failure. The one who would turn to Tor•âhꞋ must do so with urgency to break through this transitional period of isolation and aloneness before it engulfs and overcomes him or her.

He or she who has ears, let him or her hear.

Rut, Legacy of Lot?

Some say that Rut, from whom the Mâ•shiꞋakh descended, because she came from the tribe of Mo•âv, is a credit to ìåè (Lot), implying some "righteousness" in him. To the contrary, however, this notion contradicts the principle set forth in Tor•âhꞋ that each person is responsible for his or her own good and evil.

Raising up a child in Tor•âhꞋ or, hav•dâl•âhꞋ, evil accrues to the parent the corresponding good or evil, respectively. However, Lot had no influence, parental or otherwise, generations later, on Rut. The good is Rut's, not Lot's.

|

5765 (2004.10)

How did Av•râ•hâmꞋ Know

That the Three Men Were é--ä?

One of the most perplexing challenges for most people is how to know, really know, whether a person, opportunity or "leading" is of é--ä. Should you follow that person, opportunity or "leading"? Or not?

In the Christian Church, one frequently hears comments like "The Holy Spirit is leading me to'" or "What would Jesus do?" This, despite the misconceptions arising from the Christian Jesus of post-135 C.E. being the arch-antithesis of historical RibꞋi Yᵊho•shuꞋa. Yet, any objective observation of such people invariably demonstrates that such "justifications" have no intelligent basis and, consequently, are no different from their counterparts in Islam or other religions. Muslims, too, claim that Islam countenances their behavior for everything from wife-beatings and honor-killings to terrorist suicide bombings and beheadings, of Muslims as well as non-Muslims. Without a standard there can be no objective discernment.

Only Tor•âhꞋ proclaims such a standard: Dᵊvâr•imꞋ 13.2-6. This is the touchstone for any evaluation of a person, opportunity or "leading."

This still doesn't explain how Av•râ•hâmꞋ knew and referred to these three men as é--ä. From the eilonei (oaks, not plains) of Mamrei, the approaching men would have been ðöáéí òìéå (nitzavim alav; stationed above him) in the rolling hills that surrounded the oak woodlet, above him.

|

Superstitious commentators insist that these were "angels" in the guise of men. However, the text describes these three men both with the Tetragrammaton (18.1) and as àãðé (A•don•âiꞋ; 18.3), a term of respect reserved exclusively for é--ä. The text also reads ùÑÀìÉùÑÈä àÂðÈùÑÄéí; "three men," NOT "like three men." The context of the 3 preceding chapters, book-ended by the subsequent chapter, make clear that these were the 3 city-kings from the east—emissaries of KᵊdârꞋᵊlâ•ōmꞋër, Chief king of Ei•lâmꞋ, who was the primary power in the region at that time: TidᵊâlꞋ, city-king of Goy•imꞋ; AmᵊrâphelꞋ, city-king of Shi•nᵊârꞋ; and ArᵊyokhꞋ, city-king of El•â•sârꞋ (bᵊ-Reish•itꞋ 14.1), whom é‑‑ä would use to accomplish His purposes.

Further, even the most superstitious commentator is forced to admit that some instances of "angels" (îìàëéí; ma•lâkh•imꞋ) absolutely refer to homo sapien men, not angelic supernaturals—the Batman, Spiderman and Superman of yesteryear. However, the converse is not true. There is no instance in the entire Ta•na"khꞋ, in which ma•lâkh•imꞋ must be understood as angelic supernaturals. The only possible logically consistent meaning is that every instance of ma•lâkh•imꞋ in Ta•na"khꞋ refers to a homo sapien malakh é--ä; and this turns out to be true and, in every case, quite easy to defend (except to the incorrigibly superstitious).

Therefore, this passage is describing Av•râ•hâmꞋ sitting in the door of his tent, shaded from the noon sun, when he spotted three men approaching in the rolling hills above the Mamrei woodlet of oaks, just north of Khevron (corrupted to "Hebron"). So what was it about these three men that enabled Av•râ•hâmꞋ to distinguish them and cause him to describe them as é--ä? Recognizing them in the hills above him tells us that he recognized them at a distance. To remain consistently logical and scientific in our interpretation, these would have to be characteristics that you and I, if we knew what to look for, could distinguish at a distance.

Local kings or chieftains could be recognized at a distance by their entourage, perhaps by riding a decorated camel or donkey, or by their raiment. If they were local kings or chieftains, however, it would seem likely that they would have been described as such rather than as plain "men." While there were Kohan•imꞋ of é--ä in the area, e.g. Malkhi-Tzedeq, the Bible generally seems to describe them as Kohan•imꞋ of é--ä, not plain "men." Ma•lâkh•imꞋ of a Ko•heinꞋ like Malkhi-Tzedeq, by contrast, would be described simply as the "men" they were. We know from other passages that Malkhi-Tzedeq was known to Av•râ•hâmꞋ and, therefore, it is probable that he knew, and would have recognized, three ma•lâkh•imꞋ of Malkhi-Tzedeq, traveling toward him from the hills overlooking the oak woodlet of Mamrei.

Since the men were ma•lâkh•imꞋ of Malkhi-Tzedeq, and Malkhi-Tzedeq is explicitly called a malakh é--ä, his ma•lâkh•imꞋ were, accordingly, ma•lâkh•imꞋ of é--ä.

|

| Perhaps a bit spooky (Jim Carry, The Cable Guy movie) |

Of course, Av•râ•hâmꞋ realized that the three men weren't é--ä in the literal sense. Av•râ•hâmꞋ was neither irrational, an anthropomorphist nor hallucinating. But they were ma•lâkh•imꞋ of é--ä and, therefore, he addressed them and accorded them the respect as representatives of é--ä—just as you might announce the arrival of the telephone repairman at the door to your family as, "It's the phone company" or the cable guy as "It's the cable company, dear."

So we arrive at how to discern é--ä today—the same way Av•râ•hâmꞋ did (the principles that would later be codified in Dᵊvâr•imꞋ 13.2-6—logical, not supernatural = the Creator contradicting His own Perfect Laws); and this is the value of adhering uncompromisingly to a logical and scientific understanding of the Bible. Av•râ•hâmꞋ recognized these three men the same way you recognize people you know everyday. He knew that these three were from a Ko•heinꞋ whom he knew who represented é--ä. Now you're at the point where you can apply Dᵊvâr•imꞋ 13.2-6—and you can make the same determination, with the same confidence and accuracy, that Av•râ•hâmꞋ did. The outstanding questions, then, are:

Will you accord "men" who represent é--ä the same respect that Av•râ•hâmꞋ did?

Will you abandon supernatural fables and superstitions to apply Dᵊvâr•imꞋ 13.2-6 to guide your life like Av•râ•hâmꞋ did?

Many rabbis love to say that even the most prestigious rabbi today, is by contrast to Av•râ•hâmꞋ, unworthy even to carry his sandals. But I say to you that Tor•âhꞋ expects the same from you as from Av•râ•hâmꞋ and the other Biblical greats, no less. That is the legacy of Av•râ•hâmꞋ. However, this only becomes possible when you realize that Av•râ•hâmꞋ and the other Biblical greats were men like you and me, and the men Av•râ•hâmꞋ received that day were also men like you and me. Not only is it unnecessary for you to flirt with the supernatural in order to be like Av•râ•hâmꞋ, flirting with the supernatural—including mysticism and Qa•bâl•âhꞋ, Rambam corroborated—is superstitious magic, prohibited by Tor•âhꞋ.

A word about last year's commentary (below). In her high school graduation address (2004.06), my daughter, éòì (Yaeil), applied a principle from the world of physics to demonstrate how, everyday—even if they don't try and whether it's for positive or negative—each of her classmates would make a difference, everyday, that staggers the imagination. Never again dismiss, or even underestimate, the profound difference you make, for good or for bad, everyday. Here is the essence of her message.

The most known example from the Chaos theory is the butterfly effect, which is the idea that a butterfly that flaps it's wings in the air above Peking, could cause, in the following month, changes in a storm system in New York. From this we can learn two very important things. The first, and most obvious, is that our mere existence is making a difference in the world, as big or as small as that difference may be, and whether we realize it or not. Even without trying to make a difference at all, we influence the universe, so just imagine what you could do if you actually tried to make a difference. The second, and less obvious one is thinking of all the minute details that had to fall in place at the exact time and place that they did, for you, specifically, to be born where and when you were (all the things that had to happen for your parents to meet, for you to be born, etc.). When you think about it, it is truly a statistical miracle that YOU, specifically, are here right now. And this leads to the conclusion that there must be some special potential in YOU specifically, that there is in no one else, since all the little details you could never even imagine, fell in place for YOU to be where and when you are. It is therefore your duty to use all of your potential and do the best you can in this world, considering all the universe had to go through for YOU to be where and when you are.

|

5764 (2003.11)

When Are You Too Old To Make A Difference?

18.12 – åÇúÌÄöÀçÇ÷ ùÒÈøÈä áÌÀ÷ÄøÀáÌÈäÌ… åÇàãÉðÄé æÈ÷Åï

Today's youth-obsessed culture, starting their cosmetic surgeries in their late twenties to retain a youthful facade, would view Av•râ•hâmꞋ and Sarah as geezers who belong in a home and have nothing worthwhile to offer society.

Or consider a modern slant on Sarah: due to some biological anomaly the old woman had a kid and not long after that she died, as if an old lady having a kid makes any difference in the great scheme of things.

Hi, my name is Yi•rᵊmᵊyâhꞋu Bën-Avraham. That's my name according to Ha•lâkh•âhꞋ, by which I'm called up to read Tor•âhꞋ. (Bën-Dâvid is my legal family name that I took to live as much like a Jew as I could; before discovering I could convert to Judaism under Orthodox auspices and really become a Jew. I also notified the local JCC what I was doing so that no one in the Jewish community would be deceived and think I was claiming to be a Jew.)

Since my Orthodox conversion, I'm an adopted son of Av•râ•hâmꞋ and Sarah, step-brother of Yitzkhaq and step-father of Ya•a•qovꞋ-Yi•sᵊr•â•eilꞋ—and there are countless others like me. But Sarah, that old woman, died without ever having known about me or the countless others. She knew only Yi•tzᵊkhâqꞋ Âv•iꞋnu and then she died. Consider what her view might have been regarding her potential, one old lady having one child, to make a difference in the grand scheme. If you're over 30 do you ever feel like that?

You might exclaim, "But what a difference she made!" Ah, but no. You'd be mistaken. She didn't make the difference, é--ä did—the same é--ä who can make the same kind of difference through you! He doesn't change (Ma·lâkh·iꞋ 3.6). Sarah only trusted é--ä in practice.

You may retire from your occupation and live on a pension. But you never retire from serving é--ä. Even on one's deathbed the potential remains to inspire one more nëphꞋësh to serve é--ä in Tor•âhꞋ. Even after your death, the story of your life, or your writings, may produce offspring; eternal jewels in an eternal crown. Who can foresee the potential offspring nᵊphâsh•otꞋ of a nephesh like Yi•tzᵊkhâqꞋ Âv•iꞋnu?

|

5760 (1999.10)

In this weeks pâ•râsh•âhꞋ, Avi-Melekh claims not to have known the true status of Sarah and claims that, therefore, he is blameless.

There's a world of difference between ignorance and blamelessness.

In modern societies it's axiomatic that ignorance of the law is no excuse. As the Artscroll BeReishis notes, "[Avi-Melekh] expressed a not unusual sentiment: if his intentions were good, then he is automatically blameless. Judaism rejects this view. Good intentions do not purify a wrong deed. It must be measured by the standard of whether it complies with [Tor•âhꞋ]. If it is wrong [according to Tor•âhꞋ], then good intentions do not sanction it. Moreover, lack of knowledge concerning its impermissibility is itself sinful, for a person has the obligation to seek instruction." (1a.725, quoting Hirsch). Christians ignorant of this obligation are often arrogantly indignant when their ignorance leads them into offenses. Like Avi-Melekh, sincere and well-intentioned Christians expect that their "good intentioned" ignorance of Tor•âhꞋ makes them blameless. It doesn't. They could know Tor•âhꞋ by committing themselves to learn it from a

In the case of Avi-Melekh, we find that é--ä required Avi-Melekh to entreat Av•râ•hâmꞋ—the wronged party—to pray for him in order that Avi-Melekh might live (bᵊ-Reish•itꞋ 20.7). This clearly demonstrates that obtaining Av•râ•hâmꞋ's forgiveness was required of Avi-Melekh. Until Av•râ•hâmꞋ forgave him, Av•râ•hâmꞋ certainly wouldn't pray on his behalf in contravention of the corpus of Oral Law soon to be codified with the inspiration of é--ä at Har Sinai.

As Artscroll points out here, "Cf. [Tal•mudꞋ] Ma•

|

5755 (1994.10)

This parshah begins åéøà.

While Av•râ•hâmꞋ was living in Beir-Sheva, circa 2030 B.C.E. (see my Chronology of the Tanakh, from the "Big ðÈèÈä" Live-LinkT ![]() ), Ël•oh•imꞋ ðñä (nisah; test-proved) him (22.1-2). Ël•oh•imꞋ said to Av•râ•hâmꞋ, Take your beloved, one and only son, Yi•tzᵊkhâqꞋ Âv•iꞋnu, and go to Eretz Moriyah, and offer him up as an ascendance-offering upon the one har (mountain) that I tell you. Har Moriyah is the har upon which both Bat•eiꞋ- ha-Miqdash were built, beginning in 972 B.C.E. and completed in 965 B.C.E. (see again my Chronology of the Tanakh, from the "Big ðÈèÈä" Live-LinkT

), Ël•oh•imꞋ ðñä (nisah; test-proved) him (22.1-2). Ël•oh•imꞋ said to Av•râ•hâmꞋ, Take your beloved, one and only son, Yi•tzᵊkhâqꞋ Âv•iꞋnu, and go to Eretz Moriyah, and offer him up as an ascendance-offering upon the one har (mountain) that I tell you. Har Moriyah is the har upon which both Bat•eiꞋ- ha-Miqdash were built, beginning in 972 B.C.E. and completed in 965 B.C.E. (see again my Chronology of the Tanakh, from the "Big ðÈèÈä" Live-LinkT ![]() ).

).

Since the destruction of the Beit-ha-Miqdash and the genealogical documents needed for authentic Kohan•imꞋ, Israel today, like Yi•tzᵊkhâqꞋ Âv•iꞋnu (22:7), must ask, Where is the lamb for the ascendance-offering?

Av•râ•hâmꞋ 's reply presages é--ä's answer to us today (22:8): Ël•oh•imꞋ éøàä-ìå (yireh-lo; will see-to-Himself) the lamb, my son. This, the Nᵊtzâr•imꞋ believe, presages the mission of the prophesied "Suffering Mâ•shiꞋakh" as the lamb of é--ä, providing ki•purꞋ for those of Israel who are sho•meirꞋ-Torah.

Other decisive aspects of this messianic forerunner are: the lamb was caught in a thicket by its ÷øï (qeren, horn, beam or ray) and killed by others. The lamb did not jump on the altar and self-sacrifice itself.

Similar parallels can be drawn for messianic ki•purꞋ. Ribi Yᵊho•shuꞋa did not sacrifice himself as a human sacrifice (prohibited by Tor•âhꞋ). He was caught in a thicket of politics ensnarled with teachings. In the symbolism of Ta•na"khꞋ, teachings can be understood as a ÷øï of Light. In this sense, Ribi Yᵊho•shuꞋa was also caught in a thicket of politics by his ÷øï. Just as the lamb was supplied by é--ä to provide ki•purꞋ for Av•râ•hâmꞋ and Yi•tzᵊkhâqꞋ Âv•iꞋnu, so, too, é--ä has supplied His Mâ•shiꞋakh, Ribi Yᵊho•shuꞋa, to provide ki•purꞋ for sho•meirꞋ-Torah Jews—Israel—today.

Perhaps most significantly today, even while Av•râ•hâmꞋ and Yi•tzᵊkhâqꞋ Âv•iꞋnu both wondered where the lamb of ki•purꞋ was, é--ä had already provided it. Av•râ•hâmꞋ trusted only that é--ä would provide a lamb of ki•purꞋ. He had no idea what lamb, nor where or when he might find it. Av•râ•hâmꞋ trusted only that é--ä would provide it, like sho•meirꞋ-Torah Jews do today. Just as Av•râ•hâmꞋ turned around to find the ram behind him (22:13), so, too, those of Israel who are sho•meirꞋ-Torah trust é--ä to provide the lamb of ki•purꞋ, and will one day turn around and recognize their lamb of ki•purꞋ, the provision of é--ä, His Mâ•shiꞋakh, Ribi Yᵊho•shuꞋa.

These themes are reinforced in the Yom Kipur scapegoats of ki•purꞋ.

Also in the passage (22.15), we find a îìàê é--ä (malakh é--ä; malakh é--ä) that calls "from the heavens." This instance does not appear to be a mere human malakh, but rather a vision of Av•râ•hâmꞋ. Av•râ•hâmꞋ sees this îìàê é--ä ( cf. përꞋëq 18). This wasn't merely a áú-÷åì (bat qol; heavenly voice, lit. "daughter of a voice"). Av•râ•hâmꞋ recognized it as a manifestation of é--ä , thereupon renaming Har Moriyah (22.14) to éøàä é--ä

(yireh é--ä; é--ä will see).

This place was originally called ùìí (Shaleim; he remunerated / made peace) by Malki-Tzedeq (14.18), whom the Sages identify with Sheim Ben NoꞋakh. This place is today known by a hybrid of the two names: éøåùìéí (Yᵊrushâlayim, which means "See [plural] the pair of peaces!")

Utmost care must be exercised to ensure that no one equates a manifestation of é--ä with é--ä Himself. Only a finite number of aspects can be represented in a physical being. Being Infinite, é--ä cannot be a physical being since a physical being is, by definition, finite.

On the other hand, to go to the opposite extreme, asserting that the Mâ•shiꞋakh of é--ä would exhibit no aspects of é--ä clearly contradicts Tor•âhꞋ's instruction that all mankind is created in His image and, therefore, exhibits some aspects of é--ä. Since Benei Yisraeil are sons of Ël•oh•imꞋ, it is illogical to think that the Mâ•shiꞋakh would be any less than His firstborn among the brethren of Yi•sᵊr•â•eilꞋ.

Moreover, we are given this messianic example of the Seed by which "all of the goy•imꞋ of the earth shall be blessed," because Av•râ•hâmꞋ hearkened (as in shema!) to the áú-÷åì of é--ä (22:18).

|

5753 (1992.11)

22.8 — "And/then Av•râ•hâmꞋ said, 'Ël•oh•imꞋ will Himself see the lamb for the òìä (ol•âhꞋ; [fem.] ascent).'"

òìä is the fem. form of òìä (oleh; [masc.] ascent). For example, a woman making òìéä (aliyah; an ascending) to Eretz Yisraeil is an òìä (ol•âhꞋ; [fem. one who is] ascending) and a man making òìéä (aliyah; an ascending) to Tor•âhꞋ or to Eretz Yisraeil is an òìä (oleh; [masc. one who is] ascending). Thus, the lamb was considered ascending on behalf of the donor.

This was understood rather literally, perhaps primitively. The òìä was burned on the Miz•beiꞋakh, literally "òìä (going up) in smoke" with the aroma of grilled meat.

The ÷øáï (qor•bânꞋ; victim, sacrifice) for a çèà (kheit; misstep) was also called a çèà. That is, the çèà sacrifice was identified with the çèà itself. Similarly, the òìä-çèà sacrifice was associated with òìä, the "going up" (in smoke), taking the çèà with it.

As described by the Sages, é--ä's provision of the ÷øáï ram re-enlivened Yi•tzᵊkhâqꞋ Âv•iꞋnu, the willing sacrifice who presaged the Mâ•shiꞋakh, to a second life. Moreover, é--ä thereby enabled Av•râ•hâmꞋ to demonstrate the principle of vicarious ki•purꞋ. The ram provided vicarious ÷øáï, and ki•purꞋ, not only for Av•râ•hâmꞋ, but also for Yi•tzᵊkhâqꞋ Âv•iꞋnu.

It is imperative to distinguish vicarious ki•purꞋ from soteriology, which we will do in a moment. First, however, it is essential to demonstrate the efficacy of vicarious ki•purꞋ from Ta•na"khꞋ. This is conveniently provided in Tal•mudꞋ —

Tal•mudꞋ states explicitly that "the Rabbis," from ancient times, applied Yᵊsha•yâhꞋu 53 specifically to the Mâ•shiꞋakh. Ma•

Vicarious ki•purꞋ can mean either ki•purꞋ provided by é--ä (e.g. symbolized by animal sacrifice and other provisions stated in Ta•na"khꞋ) or ki•purꞋ supposedly provided by a man-god (namely Christ). The first is demonstrated to be in accord with Judaism, above; but the second is intractably contradictory to Judaism. Therefore, it is imperative that the two be rigorously distinguished from each other. Soteriology is the belief that a man-god, specifically Christ, actually accomplished and provides ki•purꞋ. This contrasts flagrantly with the Judaic tenet that Ël•oh•imꞋ alone, not a non-divine Mâ•shiꞋakh, accomplished and provides ki•purꞋ, whether symbolized by animals or various other instruments of ki•purꞋ set forth in Ta•na"khꞋ, including his agent—His Mashiakh Bën-Yo•seiphꞋ.

Soteriology, then, is rejected.

|

![]()

5760 (1999.10)

In 4.3, Elisha instructs the Jewess from Shuneim to request urns of, i.e., to adroitly make known her plight to, her ùëðåú (shekheinot; women "neighbors"). The singular of ùëðåú is ùëðä (shekheinah; fem. "neighbor"). When é--ä = é is part of this neighborhood, then the é is added to ùëðä to form ùëéðä (shekhinah; specialized fem. form of "neighboring" referring specifically to the RuꞋakh ha-QoꞋdësh)! Unless one accepts misojudaic Displacement Theology, the ùëéðä is then the collective presence of the RuꞋakh ha-QoꞋdësh in the hearts of every ùëï (shakhein; neighbor, masc. & collective) in every

Consequently, we find here an entirely new confirmation of the requirement of a min•yânꞋ, for a minimum ùëðåú (shᵊkheinut; "neighborhood") recognized to be delivered in the account of Sᵊdom is ten—which, in gi•mat•riy•âhꞋ, is also é. Thus, the min•yânꞋ (= 10 = é) represents é in in the ùëðä, enabling the ùëéðä.

Thus, we uncover in this passage an heretofore unrecognized reconfirmation of the requirement to live and pray within and surrounded by the

|

5753 (1992.11)

We should keep in mind the story of Elisha raising the son of the Jewess from Shuneim (now Arab-occupied village of Sulim, 5 km SE of Aphula) from the dead. If, in the enabling of é--ä, Elisha raised the dead, then how could one doubt that the Mâ•shiꞋakh would be less able than Elisha?

|

![]()

5755 (1994.10)

As learned in this year's Tor•âhꞋ section, forgiveness depends on restitution and asking for forgiveness. In the Christian world, forgiveness is mightily misunderstood. How many times have you heard Christians admitting that, despite the teaching of Jesus, they're unable to forgive someone? It happens all the time. What amazes me is that none ever question the correctness or validity of the Christian interpretations of the Scriptural requirements concerning forgiveness.

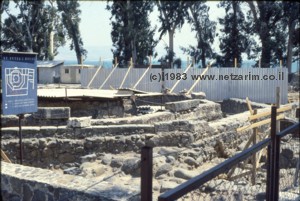

Photographing only half of the village to exclude Christian structures from centuries later allows a better perspective of the 1st-century fishing village. This was Main St., KᵊpharꞋ Na•khumꞋ, viewed from the veranda of the village Beit-ha-KᵊnësꞋët. Photograph 1983, Yirmeyahu Bën-Dawid. |

Ribi Yᵊho•shuꞋa addresses this in response to Keipha's question (NHM![]() 18.21-22): "Sir, how often shall my brother misstep toward me and I must bear him?" •marꞋ Ribi Yᵊho•shuꞋa, "I don't tell you only until seven times, but rather until seventy times seven."

18.21-22): "Sir, how often shall my brother misstep toward me and I must bear him?" •marꞋ Ribi Yᵊho•shuꞋa, "I don't tell you only until seven times, but rather until seventy times seven."

(The reference Ribi Yᵊho•shuꞋa makes in the passage cited above to "where two or three or three are gathered in my name" is referring to his authorization of the Netzar•imꞋ beit din, not a min•yânꞋ or ùëðåú—and certainly not self-appointed apostates outside of the

Oblivious to the Tor•âhꞋ guidelines underlying Ribi Yᵊho•shuꞋa's response, Christians assume this to mean that they should forgive everyone all the time.

That isn't the case.

First there is the question of who is meant by "brother." In the 1st century Jewish community in which Ribi Yᵊho•shuꞋa was teaching, his audience were religious Jews. Only Jews and and a few geir•imꞋ went to Beit-ha-KᵊnësꞋët. To those in Beit ha-KᵊnësꞋët whom Ribi Yᵊho•shuꞋa was teaching, "brother" meant fellow-Jew. Christians presume to be brothers. They aren't brothers; neither in the Scriptural context nor by Scriptural definition.

Beyond this, however, the careful reader should note that while Ribi Yᵊho•shuꞋa taught there was no limit to the number of times one should forgive his (or her) fellow-Jew, Ribi Yᵊho•shuꞋa didn't find it necessary or desirable to refine the Tor•âhꞋ criteria for forgiveness that were well-understood—in Jewish circles.

Site thought to be the house of Shimon 'Keipha' Bar-Yonah in KᵊpharꞋ Na•khumꞋ (Capernaum), where this conversation is thought to have taken place, lies beneath all of the octagonal Christian walls—that date from the 4th & 5th centuries. Part of the ancient black basalt rocks (see in other photograph) of the 1st-century walls are barely visible, protruding through the earth outside the outer octagonal wall. The octagonal Christian structures have buried half the ancient village (for other half of village, see other photograph). Since this photograph, Christians erected an even more monstrous structure over the site. Like the Muslims, Christians care only for what their religion perceives to be important, ignoring what is archeologically important to Jews. Photograph 1983, Yirmeyahu Bën-Dawid. |

The Tor•âhꞋ criteria which Ribi Yᵊho•shuꞋa assumed (contrary to the Displacement Theology of Christians) teach that only the wronged person can confer forgiveness, and then only upon a baꞋ•al tᵊshuv•âhꞋ who fulfills all, not just some, of the Tor•âhꞋ requirements for teshuvah:

demonstrates sincere remorse by making compensation plus 20% (wa-Yi•qᵊr•âꞋ 5.20-24) to the person who was wronged, and

requests forgiveness

To extend forgiveness to someone who doesn't comply with the Tor•âhꞋ requirements for teshuvah is antithetical to Tor•âhꞋ—in other words such forgiveness is an injustice and a aveir•âhꞋ of Tor•âhꞋ—and contradicts Ribi Yᵊho•shuꞋa's teaching.

As an example, for a parent or friend of a murdered victim to "forgive" the killer is unauthorized (only the victim was authorized to do that), antithetical to moral justice, represents that Tor•âhꞋ and the teachings of Ribi Yᵊho•shuꞋa are unjust, as well as betraying the victim. Lest there be any doubt, the passage cited above immediately follows Ribi Yᵊho•shuꞋa's teaching that such determinations which are made here on earth (consistent with Tor•âhꞋ criteria, obviously) are honored in the Beit-Din in the heavens (NHM![]() 18.15-20). There will be no appeal. (Interestingly, this is exactly the picture described in the Christian book of Revelation, where such appeals are made, rejected, and the appellants thrown into the lake of eternal fire.)

18.15-20). There will be no appeal. (Interestingly, this is exactly the picture described in the Christian book of Revelation, where such appeals are made, rejected, and the appellants thrown into the lake of eternal fire.)

"Forgiveness" antithetical to Tor•âhꞋ guidelines is as phony as Roman idolatry and their Hellenist man-god.

|

5771 (2010.10)

| Tor•âhꞋ | Translation | Mid•râshꞋ RibꞋi Yᵊho•shuꞋa: NHM |

NHM |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

|

![]()

![]()

Part 1 (of 6)

Great is this mi•tzᵊw•âhꞋ that Avraham Avinu began, as we memorized in be-Reishit Rabah, pâ•râsh•âhꞋ 51 (54.6) 'Then He Planted an àùì (eishel; tamarisk or grove, also an acronym for lodging and accomodations)' (bᵊ-Reish•itꞋ 21.33) of RabꞋi Yehudah and RabꞋi Nekhemyah.

•marꞋ RabꞋi Yehudah, àùì (eishel), a grove: ask whatever you wish—figs, grapes or pomegranates!

•marꞋ RabꞋi Nekhemyah said, a lodge: ask whatever you wish—wine, meat or eggs!

•marꞋ RabꞋi Azaryah, in the name of RabꞋi Yehudah in RabꞋi Shim•onꞋ, àùì, this is the Sanhedrin, as it said, And Shaul sits in Jivah under the àùì in Ramah (Shmueil Aleph 22.6).

According to the opinion of RabꞋi Nekhemyah, a lodge: Av•râ•hâmꞋ was receiving those who come and go, and to whomever would eat or drink he said to them, Bless! And they said, what should we say? He said to them, Bless Eil of the world-age of Whom is everything we eat. This is what was written, And there he called on the Name of é--ä, Eil of the world-age (bᵊ-Reish•itꞋ 21.33).

Part 2 (of 6)

And it is memorized in tractate Qama de-Sotah (10.1): 'And he planted an àùì in Beir Shava' (ibid.)

[•marꞋ Reish Laqish]: it teaches that he made a grove and planted in it all kinds of precious [fruits].

RabꞋi Yehud•âhꞋ and RabꞋi Nᵊkhemyâh, one said grove and one said lodge. Whoever says 'grove' is reasonable. This is what is written, 'and he planted.' However, whoever said 'lodge' what [rhetorically] is 'and he planted'? As it is written, 'And he planted the tents of his palace'' (Danieil 11.45).

'And there he called on the Name of é--ä, Eil of the world-age.' •marꞋ Reish Laqish, Don't read åé÷øà (wa-Yi•qᵊr•âꞋ; and he called/read) but rather åé÷øéà (wa-yaqri; and he caused to recite [which can be read without inserting the é]), teaching that Av•râ•hâmꞋ caused the Name of the Holy, blessed be He, to be recited by the mouth of everyone who comes and goes. He built an apartment and opened in it four doors to the four winds of the world-age. After they ate and drank, they stood and blessed. He said to them, And because of Whom have you eaten? None other than by Eil of the world-age have you eaten. Thank, praise and bless Him Who said and the world-age was.

Our Sages, of blessed memory, also explained thusly: àù"ì is an abbreviation for àëéìä (akhilah; food), ùúéä (shetiyah; beverage)—and there are those who say ìåéä (levayah; accompanying)] and ìéðä (linah; lodging).

Part 3 (of 6)

And it is thusly memorized in tractate Qama de-Avot: •marꞋ Yosei Bën-Yo•khân•ânꞋ, a man of Yᵊrushâlayim: Let your house be open wide and the poor be members of your household. He means to say that you should conduct your affairs in a place that is prepared for those who come and go, and let your house be always open to receive them cordially.

And it is memorized in bᵊ-Reishit Rabah, përꞋëq 66.1: "My roots are open to water and dew lodges in my branches" (I•yovꞋ 29.19). •marꞋ I•yovꞋ , by means of my wide-open doors, everyone was reaping dry [barren fields], but I—ears [of grain]. As it is said, "My roots are open to water and dew lodges in my branches." And it is said, "The geir doesn't lodge outside. I will open my doors for a guest" (ibid., 31.32).

Part 4 (of 6)

And when [guests] come to his house he shall receive them in a fair manner. And he shall immediately put bread in front of them to eat, for perhaps the poor is hungry but embarrassed to ask. Therefore, he should give him his bread and water immediately with a bright face. And if there is a matter of concern in his heart he shall remove it when in front of them and comfort them in his words. In doing this, he will be for a îùéá ðôù to them. And he shouldn't tell his weariness before them, for he will break their spirit by causing them to think that he said it for them and that he hardly has any revenue in his labor. And during dinner time he shall show himself as being sorry for not being able to attain more, as it is said: "and you shall produce for the hungry your nëphꞋësh" (Yᵊsha•yâhꞋu 58.10), meaning, My nëphꞋësh shall go out for not having more to give before you. And it is required to inquire from him what he is used to dining upon, because he might be accustomed to gourmet. If he is the son of good people, as is taught below in përꞋëq 8 from the second part (196.3). If the guests lodge with him he shall lodge them in his best beds, as is appropriate for them; because the rest of the tired is great when he reposes well. And the one who lodges him well gives him greater ease of mind than the one who feeds and quenches his thirst.

Part 5 (of 6)

And in their departure he shall escort them and give them bread for the way. Because for a loaf of bread a man may transgress. Because Yᵊhonâtân didn't give Dâ•widꞋ a loaf when he departed from him, it happened that the Kohan•imꞋ from Nov were killed. And whoever doesn't escort and give him provisions for the way, it is as if he spilled blood. As it is said: "Our hands did not spill this blood" (Dᵊvâr•imꞋ 21.7). On this it has been taught in Ma•sëkꞋët Sot•âhꞋ, përꞋëq 'Beheaded Heifer' (45b): The elders of that city wash their hands in water in the place of its beheading and say: "Our hands did not spill this blood and our eyes did not see". Is it possible that it occurred to our hearts that the elders of the Beit-Din are spillers of blood? Rather, that he did not come to our hands and we resigned him with no sustenance; and we did not see him and we left him without escort.

Part 6 (of 6)

The punishment of one who looks away from receiving guests is great. As is taught in the përꞋëq 'Portion' (Ma•sëkꞋët Sunedrion 103b): Rabi Yokhânân said on behalf of Rabi Yosei Ben Zimrâ: a morsel (food that is fed to guests) is great—it distanced two families from Yi•sᵊr•â•eilꞋ. As is said: "for not welcoming you with bread and water" (Dᵊvâr•imꞋ 23.5). Rabi Yokhânân Didyëh said: a morsel is great, for it distances the close, brings closer those who are far, looks away from the rëshꞋa, causes the nᵊviy•imꞋ of the baꞋ•al to be steeped in the Shᵊkhin•âhꞋ and making a mistake of [bread] raises insolence.

Distances those who are close—like Amon and Moâv, and brings closer those who are far, like Yitro. As Rabi Yokhânân said: In the wage of "call him and he shall eat bread" (Shᵊm•otꞋ 2.20), the sons of his sons were privileged to sit in the ìùëú äâæéú, as it is said: "and the families of authors…" (Divrei ha-Yâmim Âlëph 2.55). And it says there: "And the sons of the QiniꞋ, Mosh•ëhꞋ's father-in-law, came up from the city of dates with Bᵊnei-Yᵊhud•âhꞋ to the desert of Yᵊhud•âhꞋ, which is south of Arâd, and he went and settled the am" (Sho•phᵊt•imꞋ 1.16).

Looking away from the rᵊshâ•imꞋ, [we learn] from Mikh•âhꞋ, "… Beit ha-Mi•qᵊdâshꞋ ha-Shein•iꞋ." [We learn from] Ido, as it is written: "And he said to him I am a Nâ•viꞋ like you, and a ma•lâkhꞋ has spoken to me in the DᵊvarꞋ é‑‑ä, saying, Return him with you to your home and he shall eat bread and drink water [etc.] and as they were sitting at the table, the DᵊvarꞋ é‑‑ä came to the Nâ•viꞋ, who caused [the true Nâ•viꞋ] to return" (Mᵊlâkhim Âlëph 13.18-20). And it is written: "So he went and a lion found him on the way and killed him and his carcass was cast on the road. The donkey was standing with it and the lion stood with the carcass" (ibid, 24). So erring [about bread] costs in malice. [We learn from] Yᵊhonâtân, as Rav Yᵊhud•âhꞋ said on behalf of Rav: If Yᵊhonâtân had not lent Dâ•widꞋ two loaves of bread, the city of Nov wouldn't have been destroyed and Do•eigꞋ the EdomiꞋ wouldn't have been bothered and Shâ•ulꞋ and his sons wouldn't have been killed.

So the one who is careful in this rescues the one who comes to his house from [these bad] occurrences; and in this wage, ha-Qâ•doshꞋ, Bâ•rukhꞋ Hu, rescues him and his seed from the rigors of the world.

Google+ registered author-publisher