|

| Torâh | Haphtârâh | Âmar Ribi Yᵊhoshua | Mᵊnorat ha-Maor |

|---|---|---|---|

:23.20-21 Shᵊm•otꞋ)

äÄðÌÅä

àÈðÉëÄé

ùÑÉìÅçÇ

îÇìÀàÈêÀ

ìÀôÈðÆéêÈ,

ìÄùÑÀîÈøÀêÈ

áÌÇãÌÈøÆêÀ;

åÀìÇäÂáÄéàÂêÈ,

àÆì-äÇîÌÈ÷åÉí

àÂùÑÆø

äÂëÄðÉúÄé:

äÄùÌÑÈîÆø

îÄôÌÈðÈéå,

åÌùÑÀîÇò

áÌÀ÷ÉìåÉ

àÇì-úÌÇîÌÅø

áÌåÉ;

ëÌÄé

ìÉà

éÄùÌÑÈà

ìÀôÄùÑÀòÂëí,

ëÌÄé

ùÑÀîÄé

áÌÀ÷ÄøÀáÌåÉ:

ëÌÄé

àÄí-ùÑÈîåÉòÇ

úÌÄùÑÀîÇò

áÌÀ÷ÉìåÉ,

åÀòÈùÒÄéúÈ

ëÌÉì

àÂùÑÆø

àÂãÇáÌÅø;

åÀàÈéÇáÀúÌÄé

àÆú-àÉéÀáÆéêÈ,

åÀöÇøÀúÌÄé

àÆú-öÉøÀøÆéêÈ:

("Behold, I Myself, am sending a malakh before you to watchguard over you in the Way, and to bring you to the place that I have made ready. Watchguard yourself from his face, and hearken to his voice. Don't become bitter against him; because he will not bear your ôÌÆùÑÇò, for My Name is close-by him. For if you will hearken absolutely to his voice, and do everything that I say; then I will be the Enemy of your enemies, and the Persecutor of your persecutors.")

Some of the passages in Tor•âhꞋ contain a future significance applying to the Mâ•shiꞋakh. This is one such messianic passage. The immediate reference is to Yᵊho•shuꞋa Bën-Nun who would prepare the physical realm, Israel, whereas the messianic reference is to RibꞋi Yᵊho•shuꞋa, who would prepare a place in the eternal realm.

Interestingly, the passage also provides another instance confirming that é--ä doesn't forgive, nor will RibꞋi Yᵊho•shūꞋa bear, your ôÌÆùÑÇò.

|

|

Detractors of the Bible are wont to cite primarily from this pâ•râsh•âhꞋ (21.2-20) to claim that the Bible advocates slavery. Yet, there is no passage in the Bible that advocates enslaving anyone, only many passages addressing—and aimed at remedying—the widespread reality of slavery in ancient times. These passages range from alleviating the plight of slaves to redeeming and freeing slaves.

21.2—"You may/shall buy an òÆáÆã òÄáÀøÄé" In the past few years, some individuals have made the news by their noble-intentioned efforts to purchase slaves in Africa and then set them free. Yet, the idea comes from the Bible.

The first instruction concerning workers in this passage concerns the eventuality if one buys an òÆáÆã òÄáÀøÄé. Why would instructions concerning an òÆáÆã òÄáÀøÄé be listed first? Because an òÆáÆã òÄáÀøÄé may serve no more than six years to repay the debt of purchasing his freedom. Redeeming an òÆáÆã òÄáÀøÄé, a relative, out of slavery – perhaps from Syrians, or Egyptians – is a mi•tzᵊwâhꞋ the opposite of slavery. On the other hand, how is it different from an indentured servant of early Americans? Or different from an apprenticeship of the last century? Or even from a modern employment contract to work for a company for a specified number of years at a specified income? Clarifications concerning the òÆáÆã òÄáÀøÄé continue through pâ•suqꞋ 7, dealing with some of the complications that may arise during the period of repayment service.

In connection with 21.4, other pᵊsuq•imꞋ instruct that, unless the òÆáÆã òÄáÀøÄé prefers to keep his job and security, he has an obligation to save his money after he is freed to redeem the rest of his family.

"Maidservant" is a translation of àÈîÈä, which derives from àÅí, popularly àÄîÌÈà. Hence, àÈîÈä refers to a "motherlike maid," i.e. a nanny. One might ask why the financial interests of the owner-employer would be protected from losing an àÈîÈä (or the àÈîÈä losing her child) when the man was freed of further obligation. Keeping the child with his or her àÄîÌÈà is obvious. However, why the owner's financial interest should be protected requires a bit of thought. If the òÆáÆã òÄáÀøÄé who was close to freedom wanted to marry, an owner who stood to lose the woman and a child along with the òÆáÆã òÄáÀøÄé would be likely to refuse to allow the òÆáÆã òÄáÀøÄé to marry in the first place. This is hardly an ideal solution. It is better for the òÆáÆã òÄáÀøÄé to be allowed to marry, which means that, in order that the owner not be motivated to refuse, the owner's financial interests must be protected while still encouraging the awarding of freedom to the òÆáÆã òÄáÀøÄé and providing for the redemption of his wife and child. Most importantly, there is no advocacy of slavery in this passage.

21.21— This pâ•suqꞋ is sometimes cited as "proof" that "slaves" were treated like animals. First, "slaves" isn't a valid translation of òÆáÆã òÄáÀøÄé (which is why I keep writing òÆáÆã òÄáÀøÄé instead of "slave"). More importantly, what is the difference between the treatment of the òÆáÆã òÄáÀøÄé in pâ•suqꞋ 21 and the treatment of the ordinary òÄáÀøÄé in pâ•suqꞋ 19? The only difference is who pays whom. In the case of the òÄáÀøÄé, the one who caused the death must recompense the relatives of the deceased. Translate this identically to pâ•suqꞋ 21 and you find that the owner would be required to recompense himself—"because it's ëÇñÀôÌåÉ, the financial interest of lost income is his own rather than any income lost by relatives of the deceased. There was no monetary evaluation assessed to the loss of the deceased, as no monetary evaluation can be attached to a person. Pricing a person, as modern courts often do of a deceased, implies not only that the deceased was worth no more than some amount of cattle, automobiles, drugs or the like, and that a person can be purchased for that price.

The pâ•suqꞋ that's most often cited by misojudaics to claim that Tor•âhꞋ teaches Jews to own gentile slaves is wa-Yi•qᵊr•âꞋ 25.44. This pâ•suqꞋ refers to an òÆáÆã who is not an òÄáÀøÄé, who is from among the goy•imꞋ. Sure enough, Jews may puchase an òÆáÆã or àÈîÈä from the goy•imꞋ. But curiously, while a Jew must set an òÆáÆã free (unless the òÆáÆã chooses not to be freed), he may not sell an òÆáÆã to a non-Jew!!! That means that bringing an òÆáÆã into the Jewish system was a path to reducing slavery to a temporary period of repayment followed by freedom.

This brings us back to the man who goes to Africa to buy slaves. The news media hasn't labelled him a slaver. He redeemed the slaves he purchased, setting them free.

Yet, three thousand years before Abraham Lincoln and the American Civil War, much less Martin Luther King, it is Israel and Tor•âhꞋ that have been the perpetual champion of redeeming slaves and ending enslavement.

|

|

| Internet satellite |

Communications today, including the Internet, are arduously slow.

As recently as the mid-1980s I was doing post-grad work in computer science at the Univ. of Central Florida in Orlando. I bought my first modem, hooked it up to my brand new, out-of-the-box Apple II, and logged in to the Computer Science Department to get started on my homework – and the budding (at that time, exclusively inter-university) internet web.

Of course, I'd loaded up the computer with memory – 48 kilobytes internally plus two external drives of 143 kilobytes each! By wallowing back and forth on the external drives, I had 334 kilobytes total memory! Quite literally, I could type faster than the information was coming in over my 300 baud modem. A couple of years later, when I moved up to 1200 baud, the information was finally moving back and forth faster than I could type.

Today, most of us telecommunicate with modems in the neighborhood of 54kb (kilobaud). Still we seem to spend an inordinate amount of time waiting for information to upload or download. While most of us haven't really thought too much about it, the speed of light—the speed at which our computers work—has proven to be arduously slow when it comes to communications, transmitting information and knowledge, and even processing information within our own computers.

Here in Israel, reportedly within the next year or so, we'll be making several quantum leaps ahead in the speed of communications. Cable ISPs promise broadband access 100 times faster than today. Also available will be ADSL (asymmetrical digital subscriber line) service over telephone lines, direct satellite services and other technical advancements, all competing to provide us with faster exchange of information.

One aspect that continues to be largely ignored, however, is the increasingly daunting moral and ethical implications of web (Internet) practices. As if the world didn't already have enough swindlers, con-artists, cheats, hate-mongers and perverts, the Internet has proven an ideal petri dish spawning hoards of a new kind of shadowy and nameless "virtual" criminal. Hiding behind "handles" which conceal their true identity, these criminals and perverts spam the web with cons, hate and filth on a scale previously unimaginable.

Growing up in the late 1940s meant knowing all of your neighbors, and your neighbors knowing you—for years, and for many people perhaps all your life. One's neighbors were one's close friends. No one ever locked their doors. No one stole from their close friends—who were their neighbors. Townsfolk were "us" in contrast with "them" out-of-towners. With the advent of a mobile population and integration of various ethnic groups, working classes, religions and races people quickly began to perceive neighbors no longer as close friends, but as strangers about whom they usually knew little. "Us" stopped, and "them" began, no longer in the next town but at our own front door. Mobility enabled the criminal exposed in one place to "lose" their criminal past someplace else and begin fresh with a new supply of uninformed victims. Thus, one criminal became able to victimize a long string of neighborhoods, across counties, states, even countries.

|

The web provides instant concealment even of a criminal's present! From con-artists to misojudaics to pedophiles, criminals "anonymized" to a shadowy "handle" now do what they want with little effective opposition.

This brings us back again to the question of moral and ethical implications of web (Internet) practices. These practices begin not with web criminals, nor governmental regulations unable to span national borders to keep up with the web, but with you and me, how we conduct ourselves on the web—and Tor•âhꞋ is fully up to the task. Some examples are found here in pâ•râsh•atꞋ Mi•shᵊpât•imꞋ, e.g. (Shᵊm•otꞋ) 23.1:

ìÉà úÄùÒÌÈà ùÑÅîÇò ùÑÈåÀà

In other words, neither tolerate nor propagate an unfounded (much less false or malicious) report.

Within a geographic community, Ha•lâkh•âhꞋ requires that the facts be checked and, where necessary, the local Beit-Din issue a ruling to decide a matter. That Beit-Din's ruling is binding on all parties. On the web, where relationships and disputes cross traditional jurisdictions with impunity, which Beit-Din has jurisdiction? When a kha•reid•iꞋ rabbi in Chicago tells you (let's say you're in London) that someone in Australia is a charlatan, who, and which Beit-Din, has jurisdiction and responsibility to resolve the matter?

The answer, in my opinion, is that Tor•âhꞋ here makes it incumbent upon you, who hear the report, to be responsible to verify the facts with the source Beit-Din. The alternative is to reject the report as baseless and unreliable – lᵊshōnꞋ hâ-râꞋ. Not only may you not pass along the report otherwise, you may not even leave yourself with the doubt that the report may be true. You must make every attempt to verify the truth or falseness of the report. Putting the onus on the hearer of such reports also makes it obvious that you should be most careful to whom you listen, avoiding false reports as best you're able.

Suppose the potential victim in Australia claims to offer proof that the report about him is untrue? Similarly, the answer, in my opinion, is that Tor•âhꞋ here makes it incumbent upon you, who hear the report, to be responsible to make every reasonable effort to obtain and verify the offered proof so that you can discern the truth or falsity of the report. This cannot become the responsibility of the victim of the report. If the onus to defend against false reports is left to fall upon the victim, then those who originate the false reports win. They can simply drain the financial resources of their enemies by issuing one false report after another, forcing the victim to bankrupt himself defending himself to every individual in the world who hears the report. Clearly impossible. Once the hearer has verified the truth, it is also incumbent upon him or her to make every reasonable effort to set the record straight with others who have heard, and even among those who may be likely to hear, the false report.

|

Just as mobility once concealed criminals' pasts, cloaking oneself in anonymity by using a "handle," and often an "anonymizer" site, enables today's "virtual criminal" concealment from which to engage in their nefarious activities. Such anonymity also has broad popular appeal. Through an anonymous "handle," one can live out a fantasy in "virtual-world" as "Super-[whatever]," completely invulnerable and with complete disregard for the very real persons on the other end of the communications—you and me. It is widespread and increasing.

Update 2012: Increasingly, some of these "pretend monsters," who have practiced obsessively in virtual simulation in their dark, lonely bedrooms, are willing to trade their lives in order to experience, once in their life, a couple of hours as all-powerful in real life.

But Tor•âhꞋ deals with political correctness and following popular appeal (peer pressure) or clerical consensus – otherwise called "rabbinic majority" or consensus – too (23.2):

ìÉà-úÄäÀéÆä àÇçÂøÅé-øÇáÌÄéí ìÀøÈòÉú

While Kha•reid•iꞋ rabbis, claim, by some fabricated technicality, that (their own) slander and libel doesn't constitute lᵊshōnꞋ hâ-râꞋ, both Israeli religious attorneys and Tor•âhꞋ draw the most encompassing circle around lᵊshōnꞋ hâ-râꞋ of any of the other mi•tzᵊw•otꞋ. Only concerning lᵊshōnꞋ hâ-râꞋ does Tor•âhꞋ admonish (23.7):

îÄãÌÀáÇø-ùÑÆ÷Æø úÌÄøÀçÈ÷

|

21.1 – åÀàÅìÌÆä äÇîÌÄùÑÀôÌÈèÄéí

The Artscroll Ta•na"khꞋ editors comment here, a lesson missed by Israeli Ultra-Orthodox Kha•reid•imꞋ: "The juxtaposition of this si•dᵊr•âhꞋ (dealing primarily with civil and tort law) with the A•sërꞋët ha-Di•bᵊr•otꞋ and the laws of the Mi•zᵊbeiꞋakh provide a startling insight into Judaism. Religion is not limited to ritual and spirituality. To the contrary, all areas of life are intertwined and holiness derives from halachically correct business dealings no less than from piety in matters of ritual."

This is the basis of our reinvigorated emphasis upon the relevancy of Tor•âhꞋ to the important issues of our day, from the environment to women's rights, from drugs to abortion, et al. Our emphasis has already resulted in many articles archived in our Web Café (click in panel at left). I invite you to peruse the various issues there and suggest other issues. Help us to relate to you more personally by visiting our village Welcome Center page (click at left) and either the orientations page for Non-Jews or, for Jews, our Tᵊshuv•âhꞋ Center page. Involvement at a practical level, i.e., in practice rather than mere theory and ritual, is an integral aspect of the Nᵊtzâr•imꞋ approach, applying logic and science in practical terms and applications.

The late 20th century, and the beginning of the 21st century, have been a time of unmitigated slander and character assassination masquerading as public discussion. Tor•âhꞋ minces no words about shunning slanderers.

ìÉà úÄùÒÌÈà ùÑÅîÇò ùÑÈåÀà

Hence, a good translation of this pâ•suqꞋ is: "Don't put up with a baseless report." Tor•âhꞋ not only forbids false witness (elsewhere), it puts the onus on the hearer of a report to verify it or reject any report! (The notion of attempting to shift the onus to the victim of a baseless report is particularly ludicrous.)

Moreover, Tor•âhꞋ adds in 23.7:

îÄãÌÀáÇø-ùÑÆ÷Æø úÌÄøÀçÈ÷

Thus, this pâ•suqꞋ translates: "Distance yourself far away—remotely—from false reports." The Tor•âhꞋ Way of dealing with false reports, slander, character assassination, ad hominem, lᵊshonꞋ hâ-râꞋ and mo•tziꞋ sheim râ isn't to argue endlessly with such a person. Continuing argumentation only provides them an audience, fueling their evil slander.

Rather, Tor•âhꞋ instructs us (after a reasonable—but brief—attempt to encourage them to repent and redress their evil) to remove ourselves from their audience, to shun whomever spreads such social cancers. Avoid the temptation to ignore Tor•âhꞋ and continue arguing with a slanderer. Nothing neutralizes slanderers like being shunned, having their evil and malicious lies refused, their credibility destroyed, knowing their slander is being dismissed for the malevolent evil it is—and the thunderous silence of being ignored! Follow Tor•âhꞋ's instruction and put distance between them and you—shun them. Without an audience the malignance of their slander is isolated and they drag only themselves into the pit (gutter)—with only their slander for company.

|

This pâ•râsh•âhꞋ begins åÀàÅìÌÆä äÇîÌÄùÑÀôÌÈèÄéí which you shall place before them).

21:10—"And if he take another [wife], ùÑÀàÅøÈäÌ ëÌÀñåÌúÈäÌ åÀòÒðÈúÈäÌ shall he not diminish."

|

| Under the khupah, Yirmᵊyahu and Karen Bën-David, Eleventhmonth 25, 5744. Photograph © 1984 by Yirmᵊyahu Bën-David. |

These terms are euphemisms for marital obligations incumbent upon the man. These are the three core halakhic obligations of Jewish marriage (cf. Marriage, Jewish Publication Society, Phila.).

In each of these three nouns, the dâ•geishꞋ-pointing in the äÌ (hei) ending indicates "her."

The three core obligations toward the wife, then, are ùÑÀàÈø, ëÌÄñÌåÌé and òåÉðÈä.

òåÉðÈä can refer to either her period of abstinence from sex, commanded during her menstrual uncleanness, or her complementary period of cleanness. This principle of òåÉðÈä is understood by Ha•lâkh•âhꞋ to refer to marital attentions (including, but not limited to, sexual) from her husband—recognized in this pâ•suqꞋ as one of her three core rights.

ùÑÀàÈø and ëÌÄñÌåÌé "includes 'all necessities such as food, raiment, lodging, furniture, utensils, etc." (Marriage, 61f).

"The fourth obligation [is] the ëÌÀúËáÌÈä, which the husband must pay at any dissolution of the marriage.

"The fifth obligation concerns the payment of medical expenses in case of the wife's illness.

"The sixth obligation is for the husband to provide the money and to perform any other act required to redeem the wife from captivity.

The seventh obligation is the husband's duty to bear the costs of his wife's burial and all related expenses such as those such as those necessary for erecting a tombstone.

"The eighth and ninth obligations are the support of the widow and of the minor daughters from his estate upon his death'

"The last obligation is the inheritance by the sons of the marriage of their mother's ëÌÀúËáÌÈä, over and above their rightful portion'" (ibid.)

The four rights of the husband are also set forth in Marriage.

Readers who are married, or contemplating marriage, should apply the Ha•lâkh•âhꞋ, to the best of their ability, as set forth, for exampIe, in JPS Marriage.

|

ùÑÇáÌÈú ùÑÀ÷ÈìÄéí ([of collecting] the [Half-]shëqꞋël).

21.6 (see also 22:8) Both Judaic and Christian translators interpret this pâ•suqꞋ as "Then his master shall bring [the slave] {un}to the judges." However, look at the Hebrew! The Hebrew reads, "Then his master shall bring him to äÈàÁìÉäÄéí!!!

In this regard, see àÁìÉäÄéí in bᵊ-Reish•itꞋ 3.5; 6.4; 23.6; 30.8; Shᵊm•otꞋ 7.1; 9.28; 22.7,8, 19 & 27; 23.13; Dᵊvâr•imꞋ 14.1; Shᵊmu•eilꞋ ÂlꞋëph 2.25; I•yovꞋ 1.6; 2.1; 38.7; Tᵊhil•imꞋ 8.6; 82.6; Yᵊsha•yâhꞋu 41.23; Zᵊkhar•yâhꞋ 12.8; and Ma•lâkh•iꞋ 2.15. See also eil•imꞋ in Tᵊhil•imꞋ 89.7.

The ùÑåÉôÀèÄéí (of the Beit-Din) are called àÁìÉäÄéí in many of these pᵊsuq•imꞋ. Dâ•widꞋ ha-MëlꞋëkh wrote of an àÁðåÉùÑ; and of a áÌÆï àÈãÈí, that "åÇúÌÀçÇñÌÀøÅäåÌ a bit from the àÁìÉäÄéí" (Tᵊhil•imꞋ 8.6).

|

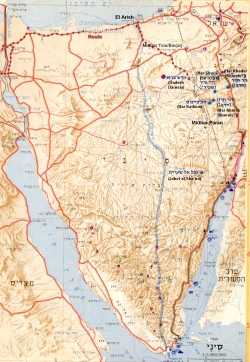

ñåÌôÇú çåÉì áÌÇðÌÆâÆá2007.05. Weaning Israel from ancient perceptions of chariots of |

Yet, (Tᵊhil•imꞋ 89.7):

ëÌÄé îÌÄé áÇùÑÌÇçÇ÷ éÇòÂøÉêÀ ìÇé--ä; éÄãÀîÆä ìÇé--ä, áÌÄáÀðÅé-àÅìÄéí?

Together, these pᵊsuq•imꞋ suggest that while humans are a little lower than äÈàÁìÉäÄéí, and that Sho•phᵊt•imꞋ are àÁìÉäÄéí, none compare to é--ä who, therefore, must be the Chief of all of the Sho•phᵊt•imꞋ, the Nâ•siꞋ of the Beit Din hâ-Jâ•dolꞋ (the Highest this-worldly Beit Din—a concept corroborating the parallel, spiritual, "Great White Throne" (actually "the Great Bench" or Seat).

A couple of references that R. Singer uses (Outreach Judaism) to make his point aren't compatible with the Hebrew and/or context. Despite the English, Shᵊm•otꞋ 7.1 doesn't say "I have made thee an àÁìÉäÄéí to Par•ohꞋ." àÁìÉäÄéí is correct, but "made" is wrong (see last month's issue of The Nᵊtzâr•imꞋ Newsletter). The verb root is ðÈúÇï, to give or allow: "I gave…" or "I allowed…" – by predesigning the moment and place of his birth, in the environment engendered by the Egyptians killing Hebrew male babies, their native Egyptian-developed mythology [he was declared by 12-year old Pharaonic Princess Khât-shepꞋset Tuth-moses to be the Egyptian god Horus-moses (the name we all know him by) retrieved from the Nile], é--ä rightly declared ðÀúÇúÌÄéêÈ ["to be" is understood in Hebrew]…

This is the way é--ä works, just as, unbeknownst to me but in my free-will earnest and enduring desire to serve Him, He prepared me from youth in the essential education and experiences, led me in the right places and to the right people that combined ðÀúÈðÇðÄé into my present place and position, áØù

Singer's point with respect to Yi•rᵊmᵊyâhꞋu 33.16, however, is valid. Pâ•suqꞋ 15 reads:

àÇöÀîÄéçÇ ìÀãÈåÄã öÆîÇç öÀãÈ÷Èä

—who "shall make mi•shᵊpâtꞋ and tzᵊdâq•âhꞋ in the land."

This definitely refers to the Mâ•shiꞋakh. By contrast, however, the next pâ•suqꞋ continues, éÄ÷ÀøÈà ìÈäÌ. This fem. pronoun, her, dictates that é--ä öÄãÀ÷ÅðåÌ in this pâ•suqꞋ cannot refer to another name for öÆîÇç (masc.), the Mâ•shiꞋakh, but dictates, rather, that the fem. pron., her, must refer to the fem. n. Yᵊru•shâ•laꞋyim. I.e., he (the Mâ•shiꞋakh) will call her – Yᵊru•shâ•laꞋyim – é--ä öÄãÀ÷ÅðåÌ.

This is, additionally, corroborated by the context: "And Yᵊru•shâ•laꞋyim shall neighbor [i.e., be a neighbor] for security, and this is what he (the Mâ•shiꞋakh) shall call her: "é--ä is our Justice."

As Singer points out (in his p. 11), pᵊsuq•imꞋ 17-18 are also Messianic. Sandwiched on both sides by Messianic pᵊsuq•imꞋ, we can be sure that pâ•suqꞋ 16 is also Messianlc.

In this context, R. Singer cites Ho•sheiꞋa 3.4-5 (Singer's p. 12a). This passage features a play on words: "Because many days éÅùÑÀáåÌ áÌÀðÅé éÄùÒÀøÈàÅì àÅéï îÆìÆêÀ (no qârbân•otꞋ, etc.).

àÇçÇø, éÈùÑËáåÌ áÌÀðÅé éÄùÒÀøÈàÅì, åÌáÄ÷ÀùÑåÌ àÆú-é--ä àÁìÉäÅéäÆí, åÀàÆú ãÌÈåÄéã îÇìÀëÌÈí;

|

| Arab-occupied Beit LëkhꞋëm. Photograph © 1983 by Yi•rᵊmᵊyâhꞋu Bën-Dâ•widꞋ. |

Bᵊn•eiꞋ-Yi•sᵊrâ•eilꞋ wouldn't request a long-dead king! (And certainly don't make request, or pray, to any dead person!)

Therefore, this refers either to a resurrected Dâ•widꞋ or, as the Judaic commentators through the ages agree, to the Mâ•shiꞋakh Bën-Dâ•widꞋ.

Given the patriarchal descent of royalty, this pâ•suqꞋ makes it a requirement—that the Mâ•shiꞋakh be a genealogical patriarchal descendant of Dâ•widꞋ ha-MëlꞋëkh. But all of the genealogies considered legitimate by the Beit Din hâ-Jâ•dolꞋ were destroyed by the Romans—except two (the patriarchal and matriarchal genealogies of RibꞋi Yᵊho•shuꞋa found in The Nᵊtzârim Reconstruction of Hebrew Matitᵊyâhu (NHM, in English)![]() ). Barring an archaeological find verified by the scientific community , there remains only one possible certain descendent of Dâ•widꞋ who could satisfy the Biblical criteria of being the Mâ•shiꞋakh—RibꞋi Yᵊho•shuꞋa. It's RibꞋi Yᵊho•shuꞋa—or no legitimate Mâ•shiꞋakh at all – forever!!!

). Barring an archaeological find verified by the scientific community , there remains only one possible certain descendent of Dâ•widꞋ who could satisfy the Biblical criteria of being the Mâ•shiꞋakh—RibꞋi Yᵊho•shuꞋa. It's RibꞋi Yᵊho•shuꞋa—or no legitimate Mâ•shiꞋakh at all – forever!!!

Of course, now that Beit LëkhꞋëm, the prophesied birthplace of the Mâ•shiꞋakh (MikhꞋâh 5.1ff), has been abandoned by Israel to Arab-occupation (and no seriously documented offspring of Dâ•widꞋ—or even serious genealogical documents—exist in our time) there can't be any other future authentic Mâ•shiꞋakh satisfying this criteria either.

|

In the last issue, we discussed how the Mi•tzᵊr•ayꞋim regarded their nobles as àÁìÉäÄéí. Soon after the Yᵊtzi•âhꞋ, we read a pâ•suqꞋ (21.6) that now comes into better focus:

åÀäÄâÌÄéùÑåÉ

àÂãÉðÈéå

àÆì-äÈàÁìÉäÄéí (and [the slave's] â•dōnꞋ shall bring him to the àÁìÉäÄéí). Glossing this over, the Koren Ta•na"khꞋ renders the English: "Then his master shall bring him to the judges." Though this does indeed refer to the Sho•phᵊt•imꞋ of the Beit-Din, Sho•phᵊt•imꞋ is not the term found in this pâ•suqꞋ. The correct connotation is "then his â•donꞋ shall present him to the àÁìÉäÄéí." As the Artscroll Stone Ta•na"khꞋ acknowledges, àÁìÉäÄéí confirms that the àÁìÉäÄéí (Sho•phᵊt•imꞋ – note that there is no capitalization distinction in Hebrew) are the representatives of äÈàÁìÉäÄéí (namely, é--ä) on earth, thereby corroborating the teaching of RibꞋi Yᵊho•shuꞋa (NHM![]() 18.19-20).

18.19-20).

This same theme applies to the same àÁìÉäÄéí in 22.27:

àÁìÉäÄéí ìÉà úÀ÷ÇìÅÌì; åÀðÈùÒÈéÄà áÀòÇîÌÀêÈ ìÉà úÈàÉø:

What are listed in si•dᵊr•atꞋ mi•shᵊpât•imꞋ are mi•shᵊpât•imꞋ. While that may sound obvious, by definition mi•shᵊpât•imꞋ are the decisions handed down by a Beit-Din. Nowhere in Tor•âhꞋ is any individual ever authorized to dispense "eye for eye and tooth for tooth" vigilante-style street justice as misojudaics routinely allege. Tor•âhꞋ is about law, not vigilantism. Appropriately, while Judaism is slandered as promoting "an eye for an eye," vigilante groups such as the Ku Klux Klan and the Neo-Nazis arise out of Christianity, espousing Christian doctrines. The WW-II Nazi effort to eradicate Jews was also based on church doctrines of a Third Holy Roman Empire (Reich) free of the "enemies of Christ/god," and consisted predominantly of church-going German Christians. Before that was the Inquisition, the Crusades, the extirpation of the Nᵊtzâr•imꞋ, and the destruction of the Beit-ha-Mi•qᵊdâshꞋ in 70 C.E.

The difference between first and second degree murder is found in 21.13-14. Contrary to popular thinking, avengers had no right to execute vigilante justice. A man wasn't a murderer until he had been tried and convicted in a Beit Din hâ-Jâ•dolꞋ (lesser courts couldn't hear capital offenses). Whereas modern courts appoint an executioner, in ancient Israel a relative of the victim carried out the sentence of the Beit Din hâ-Jâ•dolꞋ. It is ironic that those who decry Tor•âhꞋ as barbaric are the architects of a system with a misplaced compassion for lawless predators, an adversarial (not justice) system that frees the predators to stalk and kill their prey while turning law-abiding citizens of conscience and integrity into victims. (By adversarial, lawyers mean that they represent only their respective clients and the proceedings are then adversarial between the contending lawyers who are adversaries. Under the adversarial system, justice is unabashedly overridden by the lawyer's obligation to his or her client, to the exclusion of any overriding responsibility to truth or justice. While a client may admit a murder to his or her lawyer, that criminal is protected by "attomey-client privilege"obligating the lawyer to the client, not to justice.)

Speaking (in 23.31) of éÉùÑÀáÅé äÈàÈøÆõ of Kᵊna•anꞋ, 23.32 states explicitly:

ìÉà-úÄëÀøÉú ìÈäÆí – åÀìÅàìÉäÅéäÆí – áÌÀøÄéú:

De facto understandings of non-aggression are adequate. Tor•âhꞋ prohibits formal peace agreements with goy•imꞋ. The latter specifically prohibits agreements with other religions, e.g., formal relations between Israel and the Vatican. Ta•lᵊmudꞋ is silent on this pâ•suqꞋ.

The next pâ•suqꞋ, 23.33, prohibits persons of religions other than descendants of Av•râ•hâmꞋ Âv•iꞋnu from living in ËrꞋëtz Yi•sᵊrâ•eilꞋ. Thus, while Muslims are thereby excepted, Christians should not be living in ËrꞋëtz Yi•sᵊrâ•eilꞋ.

|

| 12 knee-high îÇöÌÅáåÉú (background, in 2 rows of 6) below Har Sin•aiꞋ (Har Kar•kōmꞋ, in the NëgꞋëv of Yi•sᵊrâ•eilꞋ). Courtyard separates 12 îÇöÌÅáåÉú from the mi•zᵊbeiꞋakh platform in the foreground. (www.harkarkom.com). |

24.4— "Then [MoshꞋëh] built a mi•zᵊbeiꞋakh below the har, and twelve îÇöÌÅáåÉú, for the twelve tribes of Yi•sᵊr•â•eilꞋ."

|

|

After citing other evidence for identifying Har Kar•kōmꞋ as Har Sin•aiꞋ, Anati's interviewer wrote "Even more intriguing are 12 stones fixed vertically in the ground at the foot of [äÇø ëÌÇøÀëÌÉí] itself. They are located at the edge of a camp-site from which a trail begins to the top of the mountain. Three of the stones have toppled over, but their original siting can be reconstructed. Nearby is a stone platform." (Abraham Rabinovich, "Mountain of god," JP Magazine, 87.03-27, p. 14-15).

Though archaeologist Emanuel Anati is still in the minority, Har Kar•kōmꞋ, in Mi•dᵊbarꞋ Pa•ranꞋ of the Israeli NëgꞋëv, is most likely the Biblical Har Sin•aiꞋ.

Har Kar•kōmꞋ is slightly south of the halfway-mark between áÌÀàÅø ùÑÆáÇò and Ei•latꞋ. Desert Shade Tours, operating out of Teil •vivꞋ and Mi•tzᵊpëhꞋ Ri•monꞋ, offers 4-wheel drive excursions to the site.

|

Words for today—Shᵊm•otꞋ 23.32-33:

ìÉà-úÄëÀøÉú ìÈäÆí – åÀìÅàìÉäÅéäÆí – áÌÀøÄéú:

Depending on how the Israeli-PLO Accord "negotiates out, " the resulting agreement (bᵊrit, in Hebrew) may violate this pâ•suqꞋ. If the bᵊrit to be negotiated with the PLO permits communities of Arabs to live in our land then it appears to violate Tor•âhꞋ.

It doesn't appear to me that òÇæÌÈä is included in that definition. The left- wing Labor party leading our country, however, stretch the expendable to include the Yᵊri•khoꞋ area and may compromise the Allenby Bridge and/or the Jordanian border. They give every impression that they will extend their give-away to Râm•atꞋ ha-Go•lânꞋ. But though these questions are difficult, the Gordian knot will come in Yᵊru•shâ•laꞋyim. How will any negotiated bᵊrit satisfy this requirement in Yᵊru•shâ•laꞋyim? The reason for the prohibition is given in pâ•suqꞋ 33.

|

Launch 250x194.jpg) |

Shᵊm•otꞋ 24.10: "And they saw Ëlo•heiꞋ Yi•sᵊrâ•eilꞋ, and He was making like a blue sapphire-colored moon under His Feet, and it was like the essence of the heavens for its purity of color."

Since translators have never been able to make any sense out of this pâ•suqꞋ, they have distorted it to force it into their preconceptions. The next time a space shuttle is launched from the Cape, and they show a close shot of the ignition of the rocket engines (at about T minus 3 seconds), look carefully. Underneath each rocket engine you will see an inverted, crescent-shaped, sapphire-blue flame. How would the ancients have described such a thing?

|

![]()

|

| Where is the ðÆôÆùÑ? |

Supervision of the ðÆôÆùÑ (psyche) is generally thought of (whether justifiably or not aside for the moment) as the domain of psychiatrists. When we look at the Hebrew translation, ôÌÄ÷ÌåÌçÇ ðÆôÆùÑ, however, the almost universally superficial understanding is a "life-threatening emergency." Few have bothered to look into the gaping chasm between these two definitions. Fewer still have recognized that a danger to someone's ðÆôÆùÑ is immeasurably more serious and superseding than any threat to physical life could ever be.

From the account of Dâ•widꞋ and Yo•nâ•tânꞋ we learn that in matters of survival, adroitness is a valuable attribute. This, however, raises the moral and ethical question of when, if ever, a lie is justified.

The first account to come to mind for most would be the deception which Ri•vᵊq•âh and Ya•a•qovꞋ perpetrated upon Yi•tzᵊkhâqꞋ. This is a special case in which Ri•vᵊq•âh was fulfilling a prophecy of which she was aware (bᵊ-Reish•itꞋ 25.23) and Ya•a•qovꞋ was obligated to obey his mother.

The account of Dâ•widꞋ and Yo•nâ•tânꞋ is even less straightforward. Close scrutiny, however, reveals that, while the two were adroit, no lie may be assumed.

The phrase (Shᵊm•u•eilꞋ ÂlꞋëph 20.29) ëÌÄé æÆáÇç îÄùÑÀôÈçÈä ìÈðåÌ áÌÈòÄéø. This æÆáÇç is described a bit more in Shᵊm•u•eilꞋ ÂlꞋëph 20.6 ëÌÄé æÆáÇç äÇéÌÇîÄéí, ùÑÈí ìÀëÈì-äÇîÄùÑÀôÈçÈä is more accurately translated as "for/because [there is] a qor•bânꞋ of a family life-event, there for the entire family." This referred to a Bar-Mi•tzᵊwâhꞋ, wedding or death in the family.

For an interpreter to assume there was no such family milestone event is logically unjustified and would constitute a "false report" toward Dâ•widꞋ and Yo•nâ•tânꞋ as discussed above. We must conclude, therefore, that the special event in Dâ•widꞋ's family served as the alibi for Yo•nâ•tânꞋ to—adroitly, not lying—probe his father's intentions toward Dâ•widꞋ.

Given that Dâ•widꞋ's life was imperiled, even lying would have been justified as ôÌÄ÷ÌåÌçÇ ðÆôÆùÑ. While Ta•lᵊmudꞋ is the actual source, ôÌÄ÷ÌåÌçÇ ðÆôÆùÑ is well summarized in the Encyclopedia Judaica (13.509-10): as a biblical injunction derived from the verse 'Don't [just] stand [idly] over the blood of your companion' (wa-Yi•qᵊr•âꞋ 19.16), and according to the Ta•lᵊmudꞋ it supersedes even the laws of ùÑÇáÌÈú (Ma•sëkꞋët Yōm•âꞋ 85a). One should be more particular about matters concerning danger to health and life than about ritual observances (Ma•sëkꞋët Khul•inꞋ 10a).

The rabbis interpreted the verse "And you shall keep (watchguard) My khuq•otꞋ and My mi•shᵊpât•imꞋ, which shall he do, the man shall live in them" (wa-Yi•qᵊr•âꞋ 18.5), that man shall 'live' by these commandments, and not die as a result of observing them (Ma•sëkꞋët Yōm•âꞋ 85b; Ma•sëkꞋët Sunedrion 74a). Only when faced with a choice between death and committing adultery, unlawful sexual intercourse, or murder is martyrdom to be preferred (Ma•sëkꞋët Sunedrion 74a-b). One must also sacrifice one's life rather than submit to what may be taken for renunciation of faith through the violation of any religious law in public (Ma•sëkꞋët Sunedrion 74a-b; Shu•lᵊkh•ânꞋ •rūkhꞋ YD 157). In all other cases, the rule of ôÌÄ÷ÌåÌçÇ ðÆôÆùÑ takes precedence (Ma•sëkꞋët Sunedrion 74a-b; Ram•ba"mꞋ, àÄâÌÆøÆú äÇùÑÀîÈã 3).

The rule that one may even profane ùÑÇáÌÈú in order to save the life of a person and enable him subsequently to observe many other mi•tzᵊw•otꞋ (Ma•sëkꞋët Yōm•âꞋ 85b) is inferred by the rabbis from the verse,

Shᵊm•otꞋ 31.16 – åÀùÑÈîÀøåÌ áÀðÅé-éÄùÒÀøÈàÅì àÆú-äÇùÑÇáÌÈú; ìÇòÂùÒÀåÉú àÆú-äÇùÑÇáÌÈú; ìÀãÉøÉúÈí áÌÀøÄéú òåÉìÈí:

Thus, on ùÑÇáÌÈú (or a khag), every type of medical treatment must be accorded to a dangerously ill person, to the extent of even putting out the light to help him sleep (ùÑÇáÌÈú 2.5; Shu•lᵊkh•ânꞋ •rukhꞋ, O•rakhꞋ Khai•yimꞋ, p. 278). Equal efforts must be made even where there is doubt (Ma•sëkꞋët Yōm•âꞋ 8.6; ibid. 84b). Only in cases of minor illnesses or physical discomforts should violations of ùÑÇáÌÈú be kept to the minimum. Those who are assiduous in their help, comfort, and work for the sick on ùÑÇáÌÈú, are deemed worthy of the highest praise (ibid. 328.12-13).

How much more so for the imperiled nëphꞋësh! When essential to visit an estranged Jew on ùÑÇáÌÈú who is interested in learning Tor•âhꞋ, particularly one who is shut-in, sick or otherwise doesn't attend Beit ha-KᵊnësꞋët, or a gentile desiring to learn Tor•âhꞋ, then telephoning, eMailing and even driving (which, contrary to popular misconceptions, does not involve eish) on ùÑÇáÌÈú is not only justified but particularly meritorious.

|

| Bernie Madoff (1000% Believable? Verify!) |

On the other hand, lies and deception not dictated by a genuine threat to physical survival are prohibited by the many mi•tzᵊw•otꞋ consistently requiring truth and fairness in all of one's dealings with others. This applies to the web—and email—just as in every other aspect of one's dealings with others.

Already available is encryption which countries are hard-pressed to break. What this means is that, just around the corner, is email which is secure enough to be far beyond the abilities of traditional hackers. Those few who have the ability to decrypt such sophisticated encryption won't be motivated by a couple of hundred, or even thousand, dollars or a personal argument. The beauty of the imminent encryption is that breaking it will require the efforts of a large, powerful and well-financed government, corporation or organization—which cuts out nearly all of the small-time criminals and hate-mongers which annoy iNetters today. Hackers won't succeed alone, and, having to work in coordinated groups, won't be able to operate without regulation from above. So they won't be preying upon individuals except as targetted by governments, large organizations and/or corporations.

All this means that soon most of us will be able to cut ourselves out from the "herd" of nuisance con-men, purveyors of filth, spam and hate-mongers. By your own practice on the web you get to choose whether the web will be—to you—a comic-book virtual fiction where everyone is disrespected as a similar non-person, or an invaluable communications tool between real people. You must discipline it in yourself, and require it of others as a condition of dealing/communicating with you. Each of us can refuse to deal with a shadowy character. If a person prefers a shadowy virtual existence under a pseudonym, don't deal with that non-existent "character" at all. Tell them to get back in touch when they're willing to act like, and properly identify themselves as, a person instead of a comic-book character or caped crusader. Then put a block on their character's email so it's deleted from the server without ever downloading it again. web relationships can, and should, become no more mysterious than a telephone call or neighbors chatting over their backyard fence.

|

Yi•rᵊmᵊyâhꞋu 34.19 – äÈòÉáÀøÄéí, áÌÅéï áÌÄúÀøÅé äÈòÅâÌÆì:

What is the significance of passing between the two sides of beef (probably both parties inspecting both sides)? What significance is there that one qor•bânꞋ occupies two positions, and that those covered by the one-is-two qârbân•otꞋ pass between the two parts of the one-is-two qor•bânꞋ?

The Ta•lᵊmudꞋ-corroborated teaching of two comings of the Mâ•shiꞋakh – Bën-Yo•seiphꞋ and Bën-Dâ•widꞋ – is the most reasonable inference. (This doesn't imply the unrelated Christian idol, "Christ".) Rather, as the Dead Sea Scrolls increasingly corroborate [and have since proven via (4Q) MMT], a previous coming would have to have been a Tor•âhꞋ-strict Mâ•shiꞋakh to whom the ultra-strict Qum•rânꞋ sect, increasingly linked to Yo•khân•ânꞋ 'ha-Matbil' Bën-Zᵊkhar•yâhꞋ ha-Ko•heinꞋ (cousin of RibꞋi Yᵊho•shuꞋa, and increasingly touted as a Qum•rânꞋ Essene), could relate. This precludes the Christian man-god, demonstrating that the Christian image was counterfeited outside the religious Jewish community. The implication of this is that Christianity and Jesus are a post-135 CE Roman syncretism that aren't authentic and have no legitimate origins in Judaism.

|

![]()

"Forgive our â•wonꞋ when we forgive persons their wrongs' If you forgive even the pëshꞋa of persons then your Father of the heavens will forgive your pëshꞋa. If you won't forgive persons then He won't forgive you your kheit" (NHM![]() 6.13-15).

6.13-15).

There are two constraining principles of Tor•âhꞋ to remember here:

The Christian notion of "forgiving" a guilty party for a crime against someone else (e.g. a parent "forgiving" the murderer of their child or, worse, an unrelated protestor preaching "forgiveness" of a criminal), or when the guilty party has made no repentance or attempt to make restitution, is an empty and futile perversion of the principle of forgiveness. Such contra-Tor•âhꞋ "forgiveness" precludes, and denies, Tor•âhꞋ-defined tzëdꞋëq to the victim. RibꞋi Yᵊho•shuꞋa requires that the victim of a aveir•âhꞋ of Tor•âhꞋ temper tzëdꞋëq with compassion, forgiving those who satisfy the Tor•âhꞋ requirement of tᵊshuv•âhꞋ—not perverting both the principles of tzëdꞋëq and forgiveness.

There is, however, another related passage in NHM![]() , which must also be understood. There are two kinds of aveir•âhꞋ of Tor•âhꞋ: a•veir•otꞋ against man and a•veir•otꞋ against é--ä. How can one obtain forgiveness, or know that one has obtained forgiveness, for a kheit against é--ä? The answer, of course, is trust in Tor•âhꞋ. But there are situations in which people become ill or fall victims to an accident as a result of their own feelings of guilt—their own "demons"—for some wrong they have done.

, which must also be understood. There are two kinds of aveir•âhꞋ of Tor•âhꞋ: a•veir•otꞋ against man and a•veir•otꞋ against é--ä. How can one obtain forgiveness, or know that one has obtained forgiveness, for a kheit against é--ä? The answer, of course, is trust in Tor•âhꞋ. But there are situations in which people become ill or fall victims to an accident as a result of their own feelings of guilt—their own "demons"—for some wrong they have done.

This was the situation when RibꞋi Yᵊho•shuꞋa encountered a paralyzed man in KᵊpharꞋ Na•khūmꞋ, on the northern shore of Yâm Ki•nërꞋët (NHM![]() 9.1-8), whom he recognized was suffering from such "demons" (NHM

9.1-8), whom he recognized was suffering from such "demons" (NHM![]() 9.6). When such person has demonstrated tᵊshuv•âhꞋ, which is the case when a Pᵊrush•iꞋ RibꞋi acknowledges that there is forgiveness, then Tor•âhꞋ declares the person receives ki•purꞋ and has been forgiven.

In this passage, it was clear—and stated in the text—that the paralyzed man repented and was punishing himself with his "demons" for some kheit. If it had been a kheit against é--ä, then the man would have had the assurance of Tor•âhꞋ that his tᵊshuv•âhꞋ was rewarded with ki•purꞋ and forgiveness. Thus, a priori, this was a case in which, despite the man's attempts to make restitution and obtain forgiveness from someone he had mildly wronged (with a kheit, verse 9.6), the victim refused to forgive him. In this light, one better understands the preceding passage as well.

9.6). When such person has demonstrated tᵊshuv•âhꞋ, which is the case when a Pᵊrush•iꞋ RibꞋi acknowledges that there is forgiveness, then Tor•âhꞋ declares the person receives ki•purꞋ and has been forgiven.

In this passage, it was clear—and stated in the text—that the paralyzed man repented and was punishing himself with his "demons" for some kheit. If it had been a kheit against é--ä, then the man would have had the assurance of Tor•âhꞋ that his tᵊshuv•âhꞋ was rewarded with ki•purꞋ and forgiveness. Thus, a priori, this was a case in which, despite the man's attempts to make restitution and obtain forgiveness from someone he had mildly wronged (with a kheit, verse 9.6), the victim refused to forgive him. In this light, one better understands the preceding passage as well.

It can also be seen in this light that the argument was between So•phᵊr•imꞋ and Pᵊrush•imꞋ concerning whether a RibꞋi had authority to declare a decision of Tor•âhꞋ. The Tzᵊdoq•imꞋ had only within the preceding decade lost their majority in the Beit-Din ha-Ja•dolꞋ to the Pᵊrush•imꞋ. This is confirmed in RibꞋi Yᵊho•shuꞋa's answer, "that you may see that the person has mi•nuꞋi (appointed religious position, ordainment) on the land to forgive kheit" (9.6).

Apparently, other Pᵊrush•imꞋ RibꞋis (who were – or should have been – doing similarly) were simply less able and effective than RibꞋi Yᵊho•shuꞋa.

|

| Tor•âhꞋ | Translation | Mid•râshꞋ RibꞋi Yᵊho•shuꞋa: NHM |

NHM |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

|

![]()

![]()

Although Tor•âhꞋ cautions in many places about the din (law), that din must [uphold] truth and equality of classes, [Tor•âhꞋ] was required to say that even li-shpot (to judge) truth the dayan (arbiter of law) must not take a bribe. It's impossible for him not to be swayed. The bribe will certainly become a cataract upon his eye [blinding his vision].

This pâ•suqꞋ [prohibiting the arbiter of law from taking a bribe] was written in two places—[each] following the pâ•suqꞋ 'lo tateh mishpat' (don't pervert the judgment-of-the-Beit-Din; Shᵊm•otꞋ 23.8 & Dᵊvâr•imꞋ 16.9).

This is to teach that if taking a bribe weren't prohibited except when it perverted the din, they've already cautioned [that] in the beginning; in specifically not taking a bribe. So is it superfluous [lit. why] to write [additionally], 'lo tiqakh shokhad' (don't take a bribe)? To caution that even though a man may think it won't sway the din by taking it, that he must not take it. Already, Tor•âhꞋ witnesses that it would certainly confuse [i.e. cast doubt upon] the [resulting] mi•shᵊpâtꞋ. As it is written, 'For the bribe will [operate as] cataracts [upon the eyes] of those who are [otherwise] cognizant,' etc. (Shᵊm•otꞋ 23.8)"

And it has been memorized in Siphrei…, "lo tateh mishpat." It isn't necessary to add [lit. say] 'to [pronounce] the guilty [lit. obligated] innocent or [pronounce] the innocent guilty [lit. obligated].' Rather, [the prohibition against taking a bribe holds] even [in the case of] [pronouncing] the innocent innocent or the guilty [lit. obligated] guilty [lit. obligated]. "For the bribe will blind the eyes of the wise-sages…" (Dᵊvâr•imꞋ 16.19). [Certainly,] there is no need to add [lit. say], 'the eyes of the foolish.' "and will pervert speakings of the tzadiq•imꞋ" (ibid.).

Nor is there any need to add [lit. say] 'words of the rᵊshâ•imꞋ.' Our rabbis have said, Even a wise-sage of Tor•âhꞋ [who] takes a bribe, ultimately it victimizes his opinion and he will forget his Ta•lᵊmudꞋ [learning] and the sight of his eyes will be smitten [i.e. it will impair his objectivity and judgment]. For whoever accepts a bribe it's impossible not to be influenced in his heart to reverse his innocence. As it has been memorized in Chapter Batrâ of Ma•sëkꞋët Kᵊtub•otꞋ (105.1), The rabbis have taught [lit. given], 'For the bribe will blind the eyes of the wise-sages"—so [it will] thus [blind the eyes of], all of the fools. "And will pervert speakings of the tzadiq•imꞋ"—so [it will] thus [pervert the speakings of], all of the rᵊshâ•imꞋ.

Is this something [for] fools and rᵊshâ•imꞋ, [suggesting that] they are bᵊnei-Dinâ [members of a Beit-Din]?

Rather, so he says, 'because a bribe blinds the eyes of wise-sages'—even a great wise-sage who accepts a bribe isn't dismissed from this ol•âmꞋ without having become bedazzled [i.e. cauterized] in heart.

"And will pervert speakings of the tzadiq•imꞋ"—even a complete tza•diqꞋ who takes a bribe isn't dismissed from this ol•âmꞋ without their intelligence having been victimized.

And it says in Mi•dᵊrâshꞋ, To what is a bribe analogous? To an âdâm who stands on the shore of a lake, who grasped a small worm and puts [lit. gives] it on a hook and throws it into the lake. A large fish came and swallowed it and was caught. Oy, for this fish that was caught by a nothing.

"Because the bribe will blind" (Shᵊm•otꞋ 23.8). Yet, don't some seize a bribe but don't go blind? However, they became blind to the dërꞋëkh of ë•mëtꞋ and [the sho•pheitꞋ] cannot see an obligation of the giver [of the bribe]. He has also become blind for eternity to come. The tzadiq•imꞋ are enjoying the brilliance of the Shᵊkhin•âhꞋ, as it is written, "eye to eye they shall see the return of é--ä to Tziy•onꞋ" (Yᵊsha•yâhꞋu 52.8). Everyone sees [it], but he [who took a bribe] doesn't see [it]. Everyone is healed, but he isn't healed. However, ha-Qâ•doshꞋ, Bâ•rukhꞋ Hu, says to him, 'I oversaw your creation [with good vision]. Why did you blind yourself? Why did you investigate [the principle] "Don't bend mi•shᵊpâtꞋ" and [then] bend [it]; "Don't recognize a face" [i.e. show favoritism] and then recognize [it]; "Don't take a bribe" and then take [it]?'

Yet, it wasn't enough that he damaged himself, he ruined his generation. As it has been memorized in a chapter of Ma•sëkꞋët Bâv•âꞋ Qam•âꞋ (9.2), •marꞋ Rabi Yi•tzᵊkhâqꞋ, Every Dayân who lifts up a bribe brings rough heat forever. As it is said, "and a bribe in the bosom [will cover up] rough heat" (Mi•shᵊl•eiꞋ Shᵊlom•ohꞋ 21.14). But it isn't limited to a literal bribe of a tangible asset. Rather, even a bribe of Dᵊvâr•imꞋ too. As it has been memorized in the closing chapter of Ma•sëkꞋët Kᵊtub•otꞋ (105b), The Rab•ân•ânꞋ have taught, 'And you shall not take a bribe.' It isn't necessary to say 'a bribe of a tangible asset.' Rather, even a bribe of Dᵊvâr•imꞋ is also prohibited, else it would be written, "You shall not take a questionable profit as a bribe."

Therefore, our Rabbis, the Kha•sid•imꞋ, when any man would come before them for Din and would bring them any gift—even what he was obligated to give them—or would tell them a story about bribing (what they might think [suggestible] in their heart [even if] they didn't call [it a bribe by] name; for them [they regarded recusing themselves] an obligation. Or even if they supported his opinion in the holocaust of a Din. They were conducting themselves thusly in order that the ta•lᵊmid•imꞋ would learn from them; and they were saying, "I recuse myself from your Din."

As it has been memorized in that context, what is the case of a bribe of things, because this [was the case] of Shᵊmueil, crossing at a ferry (explanation: a bridge). A noble-minded man came and gave him a hand. •marꞋ [Shᵊmueil] to him, "What is your service?" •marꞋ [the noble-minded man] to him, "I have [i.e., I'm on my way to] a Din." •marꞋ [Shᵊmueil] to him, "I recuse myself from your Din."

It was routine for the tenant-farmer of RabꞋi Yi•shᵊm•â•eilꞋ Bën-RabꞋi Yosei to bring him a package (explanation: a basket) of fruit every ascendant-day to [i.e. day preceding] ùÑÇáÌÈú. One day he brought it on the fifth day to ùÑÇáÌÈú. •marꞋ [RabꞋi Yi•shᵊm•â•eilꞋ Bën-RabꞋi Yosei] to him, "Why the difference now?" •marꞋ [his tenant-farmer] to him, "I have [i.e., I'm on my way to] a Din. I mean, since I usually come to you anyway, my sir…" "I cannot accept it" •marꞋ [RabꞋi Yi•shᵊm•â•eilꞋ Bën-RabꞋi Yosei]. "I recuse myself from your Din." He seated a pair of rabbis to [adjudicate] his Din.

With this he went and came [to and fro], •marꞋ [to himself], "If I wanted, [I could] plead such [for him], [or] if I wanted, [I could] plead such [for him]." •marꞋ, "May the bones of he who accepts a bribe decay. And [when] I, who didn't even take what was mine [was so affected], all the more so [for] one who takes a bribe?"

A noble-minded man brought to RabꞋi Yi•shᵊm•â•eilꞋ Bën-Elishâ a first-shorn fleece [reserved exclusively for a Ko•heinꞋ]. •marꞋ [RabꞋi Yi•shᵊm•â•eilꞋ Bën-Elishâ] to him, "Where are you from?" •marꞋ [a noble-minded man] to him, "From such-and-such a place." "Between there and here was no Ko•heinꞋ to whom to bring it?" •marꞋ to him, "I have [i.e., I'm on my way to] a Din. I mean, since I usually come to you anyway, my sir…" "I cannot accept it" •marꞋ to him, "I recuse myself from your Din." He seated a pair of rabbis to [handle] his Din.

With this he went and came [to and fro], •marꞋ [to himself], "If I wanted, [I could] plead such [for him], [or] if I wanted, [I could] plead such [for him]." •marꞋ, "May the bones of he who accepts a bribe decay. And [when] I, who didn't even take what was mine [was so affected], all the more so [for] one who takes a bribe?"

A noble-minded man brought RabꞋi Ânân a package (explanation: a bucket of big fish in seawater). •marꞋ to him, "What is your service?" •marꞋ [the noble-minded man] to him, "I have [i.e., I'm on my way to] a Din." •marꞋ [Shᵊmueil] to him, "I recuse myself from your Din." "Din of the sir is not the point. Accept them, sir, that they not be refused relative to [the mi•tzᵊw•âhꞋ of] bi•kur•imꞋ [designated exclusively for the Beit ha-Mi•qᵊdâshꞋ]. Tanâ•imꞋ have taught: 'And a man came from BaꞋ•al, bringing to the man of àÁìÉäÄéí bread of the first reaping…' (Mᵊlâkh•imꞋ Beit 4.42). So Elishâ [not being a Ko•heinꞋ] was eating bi•kur•imꞋ? Rather, it says to you: Everyone who brings a gift to a ta•lᵊmidꞋ-sage, it is as if he is the relative of [the mi•tzᵊw•âhꞋ of] bi•kur•imꞋ."

•marꞋ [RabꞋi Ânân] to him, "I didn't accept it as it was, but I will accept it now, since [your analogy] tells a reason [that] I [should] accept it." He sent him [to appear] before Rav Nakh•mânꞋ and sent a letter to [Rav Nakhmân]: "Prithee, sir, exercise Din for this noble-minded man. I, Ânân, have recused myself from this Din."

•marꞋ [Rav Nakhmân to himself], Sending [this] letter to me in such manner [must mean]: Hearken—implying that [the noble-minded man] is a relative of his [which is why he had to recuse himself]. [Next in Rav Nakhmân's docket, however,] was a Din [concerning] orphans. •marꞋ, "Do this or do that? Doing [the one that also produces] kâ•vodꞋ Tor•âhꞋ is preferable. He dismissed the Din of the orphans and simultaneously [adjudicated the] Din of [the noble-minded man sent by RabꞋi Ânân]. Straightforwardly favoring him, he called his adversary [instead of adjudicating the orphans' case]. [This] thoroughly disheartened [his adversary] from effectively pleading his case.

Rav Ânân was a regular of Eil•i•yâhꞋu who used to come to him and was teaching him seiꞋdër Eil•i•yâhꞋu. Because he had served [the noble-minded man], he then left. He sat in affliction and he asked for compassion and it came. Because [Eil•i•yâhꞋu] was coming [Rav Ânân] was frightened and he worked on a cubicle and he sat in it until [Eil•i•yâhꞋu] had taught him the seiꞋdërs. (There are those who say, "Major seiꞋdër Eil•i•yâhꞋu" and "Minor seiꞋdër Eil•i•yâhꞋu.") [This is] to teach us how careful man must be in mi•shᵊpâtꞋ, fleeing every hint of anything that is like a bribe, even a bribe of words; and one who does this shall never stumble.

|

|