|

| Torâh | Haphtârâh | Âmar Ribi Yᵊhoshua | Mᵊnorat ha-Maor |

|---|---|---|---|

|

(Update 2011, re: 20.8 –

Concerning bᵊ-Mi•dᵊbar′ 21.32, ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

250x364.jpg) |

thenהַמָגוֹג = הַבָּשָׁן Today's Râm•atꞋ ha-Go•lânꞋ! |

Artscroll Yechezkel (sic) notes (p. 578),

"Midrash Tanchuma to Korach (sic) points out that the numerical value of גּוֹג וּמָגוֹג is seventy, which alludes to the seventy nations of the world. The wars of [גּוֹג וּמָגוֹג] are thus projected as battles which all the seventy nations of the world will wage against Israel…"

"Yechezkel portrays Israel at the time of [גּוֹג]'s attack as a people recently gathered from exile, living peacefully within their boundaries, following agricultural and commercal (sic) pursuits, and prospering (vs. 8, 11-12)…"

"Such a description seems to assume Messianic times and, indeed, according to most sources the wars of [גּוֹג וּמָגוֹג] will take place after the first steps of the redemption – which are to be initiated by Mashiach ben Yosef, the Messiah descended from Ephraim, who is to precede the Davidic Messiah – will already have taken place." [emphasis added]

We find in Yᵊkhëz•qeil′ 38.2: "bën-

There is obvious uncertainty and confusion among the Sages where מֶשֶךְ וְתֻבָל are located, ranging from Turkey to Russia. If, at some point in its development and transitioning through different alephbeits and copying from worn scrolls with partially corrupted letters, עוֹג became confused with גּוֹג, then the discussion of גּוֹג actually referred to עוֹג – and these pair of Pᵊsuq•imꞋ then combine to tell us that הַמָגוֹג is identical to הַבָּשָׁן – today's Râm•atꞋ ha-Go•lânꞋ!

What various modern interpreters envision as far-flung future nations scattered all over the "Old World," were probably extremely remote from the calculus of Yᵊkhëz•qeilꞋ. The Nᵊviy•imꞋ likely were occupied with far more imminent threats from well-known enemies, not pie-in-the-sky, flying Egyptian winged lion gods of an imagined enemy on the far side of a globe they are supposed as having regarded being flat. The direction is the same in either case, from the northeast of Yi•sᵊrâ•eilꞋ through Râm•atꞋ ha-Go•lânꞋ or Damascus, and perhaps points continuing northeast through Syria, perhaps Turkey, and arcing eastward into Iraq (ancient Babylon) and Iran (ancient Persia). Today's global interpretations seem likely to be the fanciful product of recent centuries – and often Christian evangelists who can't read a word of the Bible.

|

19.2 – לֹא-עָלָה עָלֶיָה עֹל

|

| פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה – For some, the "Red Heifer" conjures up an image of a cartoonish, fire engine red cow straight out of Roger Rabbit's Toontown, fostering a fairy tale (fabulized) view of Bible characters and events. (This specimen would have been disqualified by some white hairs near the top of her head.) |

Last year on Shab•ât′ pâr•âh′ I included my 1992 paper, פָרָה אֲדֻמָּה (in English or Hebrew). This paper reveals the secret symbolisms of the פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה, which were lost soon after the destruction of the Beit-ha-Mi•qᵊdâsh′ and has subsequently eluded the Sages for centuries. Our 1992 paper, however, didn't cover this stipulation, which exhibits a play on words, set forth in pâ•suq′ 19.2.

Why the stipulation that the cow had never been put under a yoke? Because an animal that had "known another master," even though otherwise kâ•sheir′, was unfit to offer. This is a tenet so basic and pervasive to ancient religions that it is shared by many belief systems. The quality of having never been under the yoke of another master is manifested by such divergent evolutions as virgin sacrifices and Catholic nuns. These belief systems also associated the blood of animal and human qor•bân′ with expiation, probably along similar lines of reasoning as the מֵי נִדָּה (cf. cited paper). The מֵי נִדָּה appears to be the kâ•sheir′ parallel of virgin qor•bân′, later civilized into Catholic nuns (i.e., living virgin sacrifices spared the slaughter), in other belief systems. Conversely, Catholic nuns, having no precedent in Judaism, hearken back to virgin qor•bân′ and earlier paganism of the Romans.

|

|

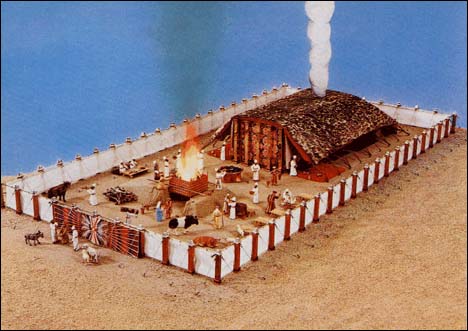

| Mi•shᵊkân′ / O′hël Mo•eid′ (model from M. Levine, Mᵊlëkhët Mi•shᵊkân′, Tel Aviv, 1968) |

This Pâ•râsh•âhꞋ begins:

וַיְדַבֵּר

19.4-5 — "And shall take Ël•â•zârꞋ the

Given our study in recent Pârâshot, the number "seven" should ring a bell. Additionally, this should be bolstered by the next phrase (v. 5): "And he shall burn the cow לְעֵינָיו. A double meaning emerges from the phrase, not just the simple meaning (i.e., "while he watches") but "עֵינָיו" referring to the seven eyes of "his"—i.e., the

|

| Mi•shᵊkân′ / O′hël Mo•eid′ |

When we begin to examine the use of עַיִן more closely, this insight proves helpful.

The first theme in Pâ•râsh•at′ Khuqat is that of the פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה.

21.7, What not to pray for— הָעָם asked Mosh′ëh to pray that

שָׂרָף is the same term Yᵊsha•yâh′u ha-Nâ•vi′ used in the plural form שְׂרָפִים. Mosh′ëh and Yᵊshayahu ha-Nâ•vi′ were describing the same thing (probably allegorically): the non-physical, 6-winged שְׂרָפִים who recite:

Yᵊsha•yâh′u 6.3 –

קָדוֹשׁ,

קָדוֹשׁ;

קָדוֹשׁ

|

|

| פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה – For some, the "Red Heifer" conjures up an image of a cartoonish, fire engine red cow straight out of Roger Rabbit's Toontown, fostering a fairy tale (fabulized) view of Bible characters and events. (This specimen would have been disqualified by some white hairs near the top of her head.) |

19.1-9 — פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה.

19.10 — The statute regarding the פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה applies also to the גֵּר.

19.11 — It is inaccurate and misleading to render the phrase:

הַנֹּגֵעַ

בְּמֵת

לְכָל-נֶפֶשׁ אָדָם

as "He that touches the dead body of any man." Rather, the meaning is "the [one who] touches the dead לְ any נֶפֶשׁ of a man." The נֶפֶשׁ shouldn't be confused with the body—alive or dead (see my articles, Neuroscience My Brain, Me and My Soul [2012.06.04] and

20.1ff — These Pᵊsuq•im′ record Israel's bivouac in the Israeli

20.8 — סֶלַע; not a small rock, nor even a boulder. This is a good place to reiterate the consistency of a logical perception of נֵס in Ta•na"kh′, relative to the accounts of Rib′i Yᵊho•shu′a and Israel's wars in 1948, 1967, at Entebbe, etc.

The popular concept of miracle as contradicting the natural / physical laws is a logical impossibility, since the the laws of physics and logic (mathematics) are the product of

The laws of nature (more specifically the laws of physics) are the product of the Perfect Creator. Therefore, these laws of nature must, likewise, be perfect. A Perfect Creator has no need to contradict (indeed cannot contradict) His own perfect laws in order to accomplish His purposes (which would necessarily imply that either His laws or His purposes were imperfect and, therefore, He is imperfect). Simply, it is self-contradicting for a Perfect Creator to contradict His own perfect laws with any supernatural phenomenon.

נֵס refers to a result that is unexpected and different from the order of things we mere mortals ordinarily perceive as expected (and, therefore, consider natural). Thus, we draw a clear distinction between something that contradicts the ordinary order as we perceive it, on the one hand, and the scientific laws of physics and nature per se. The correct way of defining נֵס, then, is an event that exceeds our understanding of the scientific laws at a given time. Most everything we take for granted in our everyday lives today would have been regarded as a נֵס in Biblical times.

Another characteristic of the Biblical definition of נֵס is that the apparent cause, even when a covert human cause may have been known to many, was ascribed to

The key factor was that the human gave the credit to

This is still the way צדקה works in the Jewish community today. Typically, the donor remains anonymous and prefers the recipient praise

No one today cites this as magic or supernatural. Yet, the נֵס of "multiplying" the oil for the widow under the supervision of Elishâ Bën-Shâphât ha-Nâ•vi′ follows this same תַּבְנִית (Mᵊlâkh•im′ Beit 4). It would have been a simple matter for the charitable neighbors, at the suggestion of Elishâ Bën-Shâphât ha-Nâ•vi′, to bring vessels full of oil, empty them into the widow's "empty" vessel while she was storing the previous vessel of oil, and then presenting the widow with the now-empty vessel she could use—quietly allowing their charity to remain unapparent so that it would not embarrass the needy widow and, at the same time, the credit could be ascribed to

After all, it was

|

We can only speculate how water was provided in this pâ•suq′. There are some things we know about water in the Middle East that might help us relate. Wells and winter rivulets were often stopped up with a boulder, to store water for the dry summer season or simply to keep animals from falling in and fouling the wells. Ya•a•qov′ unstopped a well for Râkh•eil′ (

Alternately, during the rainy winters, when rainwater drives countless small waterfalls in the mountains, pools can form behind the drop-off. Careful examination can expose a tiny stream, a drip or even a wetness on the face of the crag disclosing a potential waterfall that has been dammed at the top. Mosh•ëhꞋ himself may have ordered the damming of the waterfall the previous autumn. Prying away the rock(s) that block the water from cascading down from the waterfall can often bring a pool of water raining down.

As a matter of survival, Mosh′ëh had certainly learned this land thoroughly while with his father-in-law, Yi′tro, who was a native of the area. Mosh′ëh knew exactly where the water was and how to make it accessible—by moving a boulder with a sturdy staff as a lever.

But

However, Mosh•ëh′ either lacked – or, more likely, neglected – this trust in

The same operation of a נֵס can be inferred from Rib′i Yᵊho•shu′a's feedings of the thousands. As an Israeli from the area, Rib′i Yᵊho•shu′a knew that no one went out in the arid wilderness for a day, or a couple of days, without bread, water and a bit of food. In the vicinity of Yâm Ki•nër′ët this meant two or three fish—which, by the way, could have been perceived in cloth pouches tied around their waists aromatically rather than magically.

Rib′i Yᵊho•shu′a had faith that

How, after witnessing the first feeding of thousands, could Rib′i Yᵊho•shu′a's followers, the Nᵊtzâr•im′, doubt that Rib′i Yᵊho•shu′a could duplicate the "miracle"?

It stretches credulity beyond the breaking point to suggest that they witnessed, and then incomprehensively forgot, a 'poof' supernatural magic "miracle" like the world had never seen before. It's quite reasonable, by contrast, that in their doubt that a different crowd would respond, yet again, so unselfishly. Stated more correctly, just as Mosh′ëh doubted that

This continuation of the same approach used by Mosh′ëh stands in stark contrast to the Christian view that the divine son of god magically / supernaturally made bread and fish appear, "poof," glorifying himself as god—displacing the One

|  |

שְׂרָף עֵין גֶּדִי | שְׂרָף עֵין גֶּדִי(close-up) |

21.8-9 — "Make for yourself a שָׂרָף and put it on a נֵס." Those who were bitten by one of the שְּׂרָפִים and made it to see this נְחַש הַנְּחֹשֶׁת lived, and gave praise to

21.9 — The נֵס snake was made of copper or bronze, resulting in translations concealing a word play in the underlying Hebrew. נְחַש הַנְּחֹשֶׁת, a נָחָשׁ of נְּחֹשֶׁת. Also, the phrase "if the snake bites…" is a similar play on words: אִם-נָשַׁךְ הַנָחָשׁ.

21.32 — The English translation, "They took its hamlets," conceals two Hebrew concepts:

The verb is וַיִּלְכְדוּ. (Interestingly, this is also the shor′ësh from which the name of Israel's primary secular right-wing political party derives: the לִיכּוּד.)

בְּנֹתֶיהָ Here, "in her (fem. 'its') daughters" refers to the city's suburbs or satellite villages.

|

|

| פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה – For some, the "Red Heifer" conjures up an image of a cartoonish, fire engine red cow straight out of Roger Rabbit's Toontown, fostering a fairy tale (fabulized) view of Bible characters and events. (This specimen would have been disqualified by some white hairs near the top of her head.) |

19.1-3 — Depictions of the "red heifer" as being blood-red foster the perception of an extinct cartoon or fairy tale animal on the order of a mermaid or a unicorn. The Hebrew term אֲדֻמָּה, fem. of אָדֹם, is the general term for red. When describing soil, it means terra rosa; when describing a ranch animal, it refers to a clay-red or reddish-brown, i.e., sorrel; not cartoon or fire-engine red.

The unavailability of the פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה is not due to the extinction of a fairy tale animal, but to the destruction of all of the genealogical records of the

It is instructive that pâ•suq′ 3 directs Mosh′ëh and A•har•on′, the

Still, however, to err on the side of safety, the constraints regarding marriage and the like apply to those families who are, by tradition only, thought to be

Some opinions registered in

The Soncino

However,

The distinction was raised because the פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה had no connection to the מִזְבֵּחַ

This service of the

"The real thing" is officiated in this non-dimensional Realm before the Throne of

|

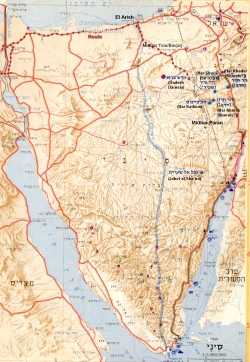

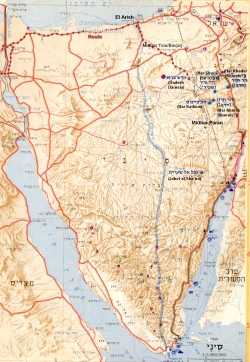

20.22 — "And they traveled from Qâ•deishꞋ and

On the map shown, Qâ•deishꞋ (variously corrupted to Qadesh-Barnea / Kadesh Barneya) is located 7 km on the Mi•tzᵊr•ay′im side of the

The Har•im′ discussed below (spellings from אטלס סיור וטיול בישראל)

are in the same general area, 33 km due south of Mi•tzᵊpeihꞋ Râ•monꞋ (2 א-ב, between English transliterations "Shazar" & "Se'ir"). See also Firstmonth 1st in the Bible, in our Calendar page.

This correlates with detouring around

|

| Reed marshes on bank of the Nile. Note higher ground in background, evidenced by trees. |

It wou]d seem from the Biblical description that Bᵊnei-Yi•sᵊr•â•eil′ made their Yᵊtzi•âh′ from Mi•tzᵊr•ay′im through the marshy (reedy) area near the northern mouth of today's Su•eitzꞋ canal. Emerging from this marshy area, in which Par•oh′'s chariot force was subsequently swamped during the Santorini volcano eruption, ca. B.C.E. 1467-53), Bᵊnei-Yi•sᵊr•â•eil′ traveled east along the northern coast of

This is also corroborated in that the annual autumn migration of quail make shore exhausted, falling to the ground where they can be captured by hand or with nets, near Ël A•rishꞋ; 1-ג), northwest of Qâ•deishꞋ. (Cf. Shᵊm•ot′ 16.13 and bᵊ-Mi•dᵊbar′ 11.31-2.)

Moreover, one of the campsites, בַּעַל צָפוֹן (cf.

Another campsite, רִמֹּן פָּרֶץ (

The traditional "southern route," and the traditional "Mt. Sinai" picked out by a 4th century Christian queen (Catherine), is recognized among virtually all archeologists, historians and related scholars as meritless.

From the area of Ël A•rishꞋ on the northern coast of the

|

This places:

הַר שֵׂעִיר, likely corrupted to today's הַר שַׁזָר—easily mistakable by copyists in worn, ancient Hebrew mss. having an illegible or missing letter:

Unlikely to mistake in Proto-Sinaitic Hebrew:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() to

to ![]()

![]()

![]()

In Middle Semitic Hebrew, a missing ע plus a worn or damaged י:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() to

to ![]()

![]()

![]()

In 1QIsa (Isaiah Scroll) Hebrew, easiest to mistake: ע and י close together, where י and branch of ע become worn or damaged and no longer visible

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() to

to ![]()

![]()

![]()

הַר חוֹרֵב, later spelled הַר חֹרֶב, probably miscopied as today's הַר חָדָב

Unlikely to mistake in Proto-Sinaitic Hebrew:

![]()

![]()

![]() to

to ![]()

![]()

![]()

In Middle Semitic Hebrew, easy to mistake: ר and for ד:

![]()

![]()

![]() to

to ![]()

![]()

![]()

In 1QIsa (Isaiah Scroll) Hebrew, easy to mistake: ר for ד

![]()

![]()

![]() to

to ![]()

![]()

![]()

and הֹר הָהָר — Arabized to הַר הָרוּן as today's הַר חֲרוֹז

The similarity of these names in Hebrew correlating to the geographic cluster of these named mountains is striking, and such evolutions of the names could easily have occurred over the centuries of copying mss. By contrast, the probability that all of these mountains would be in such proximity to each other, in the direct route described here, and have names so similar to the Biblical names cannot reasonably be attributed to coincidence.

|

What continuity is implied in the juxtaposition of the story of the מִין of QoꞋrakh adjacent to the story of Mosh′ëh disobeying by striking the rock?

Seeing past the magical interpretations so often loaded onto this passage, one can picture Mosh′ëh being told to merely speak to the rock and it would bring forth water. How? Magically? No moreso from an Unchanging

[2002: Moreover, in prying away the boulder himself, Mosh′ëh pre-empted someone's opportunity to demonstrate trust in

QoꞋrakh had asserted that all of the convocation was holy and that Mosh′ëh was presumptuous in placing himself above the rest of the holy kindred. Here, Mosh′ëh is shown that, although QoꞋrakh's approach was intolerable, there had been some truth in QoꞋrakh's complaint. And isn't it the grain of truth in the message of most min•im′ that makes them so effective?

Mosh′ëh hadn't adequate confidence in the holy kindred to take Him at His Word and let them dig for the water themselves. Mosh′ëh was overly presumptuous after all. And so he was punished for his presumptuousness by being barred from entering Yi•sᵊr•â•eil′.

|

Openings to pockets of water in the

In 20.7-8,

|

19.2 – וְיִקְחוּ אֵלֶיךָ, פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה, תְּמִימָה, אֲשֶׁר אֵין-בָּהּ מוּם, אֲשֶׁר; לֹא-עָלָה עָלֶיָה עֹל

Judean Hills 354x251.jpg) |

Israeli red clay (terra rosa) in Judean Hills. |

The Hebrew term אדמה (admh) is vowel-pointed by Masoretic tradition dating back only to the 7th century C.E. However, the Muraba'at (area of Dead Sea) scrolls offer some evidence that this tradition may have been fixed by 132 C.E. According to this vowel-pointing, the word is אֲדֻמָּה (fem. of אָדֹם). Interestingly, the word derives from the same stem as אֲדָמָה, a cognate of אָדָם, which likely derived from דָּם.

As such, אֲדֻמָּה and [the spilling of] דָּם are closely associated with, and often used to symbolize, the imperfections of uncleannesses in אָדָם.

The פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה symbolized the אֲדָמָה as well as אָדָם who was formed from אֲדָמָה and, in death, returns to it.

In fact, this whole process of coming from אֲדָמָה and returning to it can be seen in this ritual.

Additionally, the פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה was required to be whole / perfect (as opposed to defective) and without any מוּם, either of which would render it imperfect.

One must distinguish between the symbol or pattern and the real thing. Who would confuse a blueprint with the real building?

Though obedience to these laws of תּוֹרָה did indeed provide expiation, it is not difficult to recognize that sacrificing these animals could not be the real vehicle—endorsed by an Omni-intelligent Creator of the laws of physics, mathematics and logic—for filtering and removing imperfections from a human psyche.

The purpose of the qor•bân•ot′ closely parallels stiff monetary penalties handed down by law courts today. Beyond the qor•bân′ aspect, the animals merely symbolized the principles, serving as a pattern for our understanding, of the real expiation—which

|

| פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה – For some, the "Red Heifer" conjures up an image of a cartoonish, fire engine red cow straight out of Roger Rabbit's Toontown, fostering a fairy tale (fabulized) view of Bible characters and events. (This specimen would have been disqualified by some white hairs near the top of her head.) |

If this פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה, which was to be an expiatory qor•bân′, was imperfect while symbolizing the imperfections of the nëph′ësh (i.e., sin), then it would not be the perfectly sinless vessel (qor•bân′) required to "absorb" man's sins and carry them off to Shᵊ•ol′ through the various methods of assignation (e.g., sprinkling or laying on of hands while confessing the sin for which the qor•bân′ was being made).

In the same vein, if this פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה had already borne burdens of man, toiling under man's yoke, then it was not the perfectly "burdenless" instrument necessary for bearing the burden of man's sins to Shᵊ•ol′.

The תַּבְנִית shows clearly that

The תַּבְנִית shows another striking lesson that is universal throughout the Ta•na"kh′: failure to follow the instructions of

Tor•âh′ shë-bi•khᵊtâv′ prescribes the limits of interpretation by Jewish religious leaders. No amount of rabbinic legislation or any other power can ever change this basic requisite. Since

The ramifications are far-reaching. It may someday be possible to build another Beit-ha-Mi•qᵊdâsh′ and Miz•bei′akh on Har ha-Ba′yit. But Ta•na"kh′ requires that qor•bân•ot′ only be made by

While some specious demagogues (nearly always Ultra-Orthodox) claim to possess such documents, they uniformly refuse to submit their alleged documents to scientists for verification. Historical documents show that, by the 4th century C.E., the Romans destroyed all of the genealogies so that none remained either for ![]() 1.1-17).

1.1-17).

Moreover, the services & qor•bân•ot′ of the Mi•shᵊkân′ and Beit ha-Mi•qᵊdâsh′ hâ-Rishon were endorsed by the Shᵊkhin•âh′—the kâ•vod′-י--ה, as attested by all of Israel, who were all eyewitnesses.

There was no such endorsement by

Building another Beit-ha-Mi•qᵊdâsh′ and Miz•bei′akh on Har ha-Ba′yit wouldn't be valid or legitimate unless the endorsement of the Shᵊkhin•âh′ were witnessed by all of Israel—not merely the loopy claim of some fanatic that we should trust his testimony instead of keeping-תּוֹרָה!

At least until the advent of the Mâ•shi′akh, who must provide non-existent documentation of his pedigree to Dâ•wid′ ha-më′lëkh (unless the Mâ•shi′akh is Rib′i Yᵊho•shu′a, whose pedigree is preserved), expiation through blood qor•bân′ is totally impossible! One is expected to have already learned from these patterns the real and eternal provision for expiation which

19.3 – וּנְתַתֶּם אֹתָהּ, אֶל-אֶלְעָזָר הַכֹּהֵן; וְהוֹצִיא אֹתָהּ אֶל-מִחוּץ לַמַּחֲנֶה,

Note first that a documented

Why did the פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה have to be taken outside of the camp for this ritual? Because death-contamination, not permitted in the camp, was a primary factor of this ritual. Burning of the פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה reduced to its essence—ashes—the main ingredient needed to formulate מֵי נִדָּה, which was considered able to cleanse and flush away death-contamination.

While the ashes from this מוּם-free פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה were then a perfect vehicle to absorb death-contaminations, the area in which the qor•bân′ was made symbolized a dump, through which death-contamination was being channeled and dissipated in the vicinity. This is evident from pᵊsuq•im′ 7-9 since the death-contamination had been dissipated leaving behind only "death-contamination absorbent" ashes, probably white – indicating successful purification (cf. Yᵊsha•yâh′u 1.18). Yet, the

This is also evident from the remark in pâ•suq′ 9 to "lay them outside the camp" (still, or but) "in a clean [

19.6 – וְלָחַק הַכֹּהֵן, עֵץ אֶרֶז, וְאֵזוֹב וּשְׁנִי תּוֹלָעַת; וְהִשְׁלִיךְ אֶל-תּוֹךְ שְׂרֵפַת הַפָּרָה:

Some Talmudic sages have attempted to link this ritual of the פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה with the Pës′akh qor•bân′ because both are termed חֻקָּוֹת, concluding, in true rabbinic non-sequitur, that, therefore (!), one enables or derives from (depending upon the commentator) the other. This is roughly parallel to concluding that prayers at the

250x165.jpg) |

שָׁנִי תּוֹלַעַת (usually תּוֹלַעַת שָׁנִי) – Coccus ilicis – belongs to the Coccidae or Scale-insects, and its species are common on oaks wherever they grow. As in the case of other scale-insects, the males are relatively small and are capable of flight, while the females are wingless. The females are remarkable for their gall-like form.

In the month of May, when full grown, the females are globular, 6 to 7 mm. in diameter, of a reddish-brown color, and covered with an ash-colored powder. They are found attached to the twigs or buds by a circular lower surface 2 mm. in diameter, and surrounded by a narrow zone of white cottony down. At this time there are, concealed under a cavity formed by the approach of the abdominal wall of the insect to the dorsal one, thousands of eggs of a red color, and smaller than poppy seed, which protrude in a regular array beneath the insect.

At the end of May or the beginning of June the young escape by a small orifice, near the point of attachment of the parent. They are then of a fine red color, elliptic and convex in shape, but rounded at the two extremities, and bear two threads half as long as their body at their posterior extremity. At this period they are extremely active, and swarm with extraordinary rapidity all over the food plant, and in two or three days attach themselves to fissures in the bark or buds, but rarely to the leaves.

In warm and dry summers the insects breed again in the months of August and September, according to Emeric, and then they are more frequently found attached to the leaves. Usually they remain immovable and apparently unaltered until the end of the succeeding March, when their bodies become gradually distended and lose all trace of abdominal rings. They then appear full of a reddish juice resembling discolored blood. In this state, or when the eggs are ready to be extruded, the insects are collected." (encyclopedia.jrank.org; 2012.06.24).

The extract from the תּוֹלַעַת שָׁנִי was used for dyeing curtains of the

Mᵊtzorâ•im′, considered 'death-contaminant walking' and, therefore, similarly a death-contaminant, like the ritual of the פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה, were barred from the camp.

|

Like the פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה ritual, cedar wood was used as well as תּוֹלַעַת שָׁנִי extract in the mixture (along with water and blood) for purifying mᵊtzorâ•im′.

Further, in both cases the ritual is one of purification after

It is not unlikely that the subcutaneous infestations of tzâ•ra′at—sometimes containing live and visibly moving larvae—were viewed as similar to the worm-infestations they had undoubtedly witnessed in dead bodies, and believed it to be evidence that parts of the victim were dying or dead – a contamination of death. Thus, the remedy was viewed as similar: the פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה ritual.

|

This is a protected plant in Israel — strictly enforced with large fines. (photo © Martha Modzelevich; flowersinisrael.com) |

The use of cedar and אֵזוֹב in both rituals serves to reinforce the connection between these rituals, since cedar is one of the most fragrant of woods and אֵזוֹב "is effective in counteracting an offensive odor" (R. Samuel Sarsa on Ibn Ezra's comment to Shᵊm•ot′ 12.22; Ency. Jud. 8.1148) that would be associated with the uncleanness of both tzâ•ra′at and the dead.

Neither should the connection be lost between death and the passing over by the angel of death at Pës′akh with the use of אֵזוֹב in both.

19.9 – וְהָיְתָה, לַעֲדַת בְּנֵי-יִשְׂרָאֵל לְמִשְׁמֶרֶת, לְמֵי נִדָּה, חַטָּאת הִוא:

The qor•bân′ of the פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה served as a watchguard of purity among the children of Israel, the ashes ready to be brought out at any time there was need and mixed with water to make מֵי נִדָּה.

Since these waters are never used in connection with a menstruous woman it logically implies a different connection. Before exploring this, however, the added significance of adding extract of crimson should be noted.

Many similarities beyond these have been found by the sages connecting menstruation with death. Essentially, menstruation represents the death of an egg (or, at least, a potential human life). The connection between banning menstruous women, mᵊtzorâ•im′ and those unclean from touching the dead is thus resolved to a common thread. These waters of purification (containing ash from the פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה) are here referred to metaphorically as מֵי נִדָּה.

19.10 – וְהָיְתָה לִבְּנֵי-יִשְׂרָאֵל, וְלַגֵּר, הַגָּר, בְּתוֹכָם, לְחֻקַּת עוֹלָם:

It should be noted that, like the entirety of the patterns in the Ta•na"kh′, this is a pattern of something that would accrue only to

19.21 – וְהָיְתָה לָהֶם לְחֻקַּת עוֹלָם; וּמַזֵּה מֵי הַנִּדָּה יְכַבֵּס בְּגָדָיו וְהַנֹּגֵעַ בְּמֵי הַנִּדָּה, יִטְמָא עַד-הַעָרֶב:

Upon mixing and application, the מֵי נִדָּה symbolically absorbed the death-contamination, becoming a contaminant.

While sages have been baffled for centuries attempting to explain the meaning of this ritual of the "red heifer", here it is stated in the clearest possible terms! The waters of the פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה are seen as menses, the only phenomenon in nature which flushes away death (from the woman—the presumed-dead egg). While it required a

20.7-8 –

וַיְדַבֵּר

In the subsequent

Worse, Mosh•ëh′ implied that the convocation was rebelling against him rather than against

The Sages through the ages have largely regarded the symbolism of the פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה not merely as a mystery, but as a mystery that must remain unknowable until revealed by the Mâ•shi′akh. That's a convenient contradiction of תּוֹרָה (

No overall symbolic structure is found in the literature. Yet, the keys to relating to the meaning of this rite of purification have long been known. That this symbolism has now been revealed is more than a little unsettling to them. It implies that the Mâ•shi′akh has come!!!

|

| פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה – For some, the "Red Heifer" conjures up an image of a cartoonish, fire engine red cow straight out of Roger Rabbit's Toontown, fostering a fairy tale (fabulized) view of Bible characters and events. (This specimen would have been disqualified by some white hairs near the top of her head.) |

It is well established that the ashes of the פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה were mixed with cedar, crimson and ei•zov′ to produce a reddish water used for the purification of persons and objects which had been defiled through contact or association with death.

The Sages also noted that this reddish water closely resembled that used in the purification of the recovered mᵊtzor•â′. In the former the cedar, crimson and ei•zov′ were mixed with water while in the latter the cedar, crimson and ei•zov′ were mixed with the blood of a dove. In each case the vehicle of purification was a reddish solution resembling—and, in some cases, sometimes containing—blood.

This blood-like solution in the case of the פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה is called מֵי נִדָּה (bᵊ-Mi•dᵊbar′ 9.9, 13, 20, 21). This phrase was intended as a key to understanding the meaning. While this in itself suggests association with the woman who is nid•âh′, there are other connections as well. It is a well established principle in Judaism that the proximity of subjects in תּוֹרָה often suggest a relationship between them. This is the case with the recovered mᵊtzor•â′ and the woman who is nid•âh′ (wa-Yi•qᵊr•â′ 14-15). There is good reason for this proximity.

While we have noted the connection between the mᵊtzor•â′ and the פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה, the connection of these with the woman who is nid•âh′ is more subtle. This connection is to be seen in the type of defilement common to all three—defilement associated with death. This purpose is given for the case of the פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה. In the case of the mᵊtzor•â′, a mᵊtzor•â′ is accounted as dead, ''as it is written, '[And A•har•on′ looked upon

But how is the woman who is nid•âh′ associated with death, thus tying the three together? Menses is the only phenomenon in nature which washes away death (the dead egg, which was presumed dead). It was recognized that the onset of the woman's menstrual cycle somehow signaled the death of a human life – which has implications, heretofore unrecognized by the rabbis, regarding the infanticide (abortion) issue.

Today we would characterize this as the expelling of a human egg. But the theme holds, nevertheless. It was not her flow of menstrual blood that defiled the woman. On the contrary, just as the מֵי נִדָּה of the פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה cleansed the person or object who had become defiled by contact with death so, too, the מֵי נִדָּה of the woman cleansed her of her contact with the death of that potential human life. In all three cases, contact with the dead required seven days of purification, by similar rituals, and by the instrument of מֵי נִדָּה!

This suggests that the purification ritual of the פָּרָה אֲדֻמָּה for objects and persons who had become defiled by contact with death and the purification ritual for the recovered mᵊtzor•â′, who was as dead, were patterned after the natural purification of the woman, which has implications concerning women as a תַּבְנִית in early symbolism. These purification rituals can then be readily understood as a symbolic washing away of the tokens of death in the מֵי נִדָּה.

|

![]()

Any analysis of the efficacy of Yi•phᵊtâkhꞋ's nëd′ër, and his performance of his nëd′ër, hangs from the thread of historical context; freed of anachronistic, medieval European perspectives that have been projected back on the ancient Sho•phᵊt•im′.

The Sho•phᵊt•im′, it should be remembered, succeeded Yᵊho•shu′a Bën-Nun immediately following the conquest of Kᵊna•an′. Upon the death of Yᵊho•shu′a Bën-Nun, the first Sho•pheit′ governed ca. B.C.E. 1394. Yi•phᵊtâkhꞋ was the ninth sho•pheit′, governing, perhaps only regionally, ca. B.C.E. 1137-32. During this period, positions concerning nᵊdâr•im′, the

While outlying temples disappeared with the building of the Beit-ha-Mi•qᵊdâsh′ (B.C.E. 980), family and tribal altars were maintained for centuries after, as evidenced by the strong condemnations against them. In the times of the Sho•phᵊt•im′, the eldest living family and tribal patriarchs were the officiating priests on their family and tribal altars. As the Sho•pheit′ of Israel, Yi•phᵊtâkhꞋ was the top priest, not only in his own tribal province of Gi•lᵊâdꞋ, in present day Jordan, east of the Nᵊhar′ ha-Yar•dein′, but in Israel overall.

|

Ignorance persists due also to confusion of several villages, at different times, with the same names. While there is a "Mizpeh" near Beit Eil known today, this "Mizpeh" didn't exist in the time of Yi•phᵊtâkhꞋ. Yi•phᵊtâkhꞋ governed from the Gi•lᵊâd•iyꞋ village of

Beit Eil, by contrast, was a village of "crude" buildings located 17km (10½ mi.) N. of Yᵊrushâlayim in the vicinity of modern Beit Eil, on the southern border of the tribal province of Ë•phᵊraꞋyim (Yᵊho•shu′a 16.1-2; 18.13; Divrei ha-Yâmim Âlëph 7.28), but also listed as a border-village of the neighboring tribal province of

In short, Beit Eil was never regarded as amphictyonic and Pi•nᵊkhâsꞋ ha-Ko•hein′, even though he was empowered to invoke the oracle of the Ur•im′ wᵊ-Tum•im′ (Sho•phᵊt•im′ 20.18,20) would never have dreamed of contradicting תּוֹרָה with an innovation not even conceived until a millennium later.

With this in mind, we can evaluate the Mi•dᵊrâsh′ position that Yi•phᵊtâkhꞋ could simply have gone to Pi•nᵊkhâsꞋ ha-

Thus, Yi•phᵊtâkhꞋ ha-

Because excluding the popular explanation as an impossibility leaves an unknown void, it begs a plausible explanation. Such a solution is suggested in other precedents: the accounts of Mosh•ëh′ striking the rock and Shimshon (corrupted to "Samson") intermarrying. Yi•phᵊtâkhꞋ's nëd′ër was a carelessness and near-horrific error that Israel must remember and learn from. (However, see the '•mar′ Ribi Yᵊho•shu′a' section.)

Despite the conspicuous lesson, the first recorded doubt about Nᵊdâr•im′ isn't expressed until centuries later, in Qo•hël′ët (5.3-4; ca. B.C.E. 7th-3rd century). Interpretations of this passage ranged from "Better is he who vows and pays" to "Better than both is he who does not vow at all"—the view articulated by Beit-Hi•leil′, advocated by Rib′i Yᵊho•shu′a (see '•mar′ Ribi Yᵊho•shu′a' section). "The weight of opinion, however, especially in the

|

![]()

| Nᵊviy•im′ | Translation | Mid•râsh′ Rib′i Yᵊho•shu′a: NHM |

NHM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Haphtâr•âh′ Shoph•tim′ 11.1-40 | Nëd′ër Yi•phƏtakh′ | Nëd′ër (Herod) | 14.3ff |

|

![]()

|

| "Queen (reverse of husband, King Aristobulus', coin) Depiction: Inscription: ΒΑCΙΛΙC ΣΑΛΩΜΗ ( |

The same catastrophic recklessness exhibited by Yi•phᵊtâkhꞋ's nëd′ër, carrying such tragic consequences, is echoed in the 1st century C.E. in King Herod's nëd′ër to his step-daughter, ![]() 14.3ff).

14.3ff).

As pointed out in the Haphtâr•âh′ section this year, Rib′i Yᵊho•shu′a advocated the majority opinion (NHM![]() 5.33-37): "Again you've heard the Oral Law concerning: 'Don't perjure yourself swearing in My Name' and 'You shall render to

5.33-37): "Again you've heard the Oral Law concerning: 'Don't perjure yourself swearing in My Name' and 'You shall render to

|

![]()

There is another greatness, even greater than these, in the differentiation of תּוֹרָה, that it's inappropriate for a man to promote [himself]; and, if he pursues that, then it eludes him; but if he humbles himself in it, ha-Qâ•dosh′, Bâ•rukh′ Hu, upgrades him.

As it has been memorized in part 141 of Eiruvin (13.2), •mar′ Rab′i Aba Shmueil, 'Three years Beit-Sha•mai′ maintained Havdâl•âh′ from Beit-Hi•leil′. These said, 'The Ha•lâkh•âh′ is like ours' and those said, 'The Ha•lâkh•âh′ is like ours.'

A Bat Kol went forth and told them, 'These and those are [both; note this contradiction is a logical impossibility] the Oral-Sayings of the Living Ël•oh•im′, but the Ha•lâkh•âh′ is that of Beit-Hi•leil′. And why did Beit-Hi•leil′ merit to fix Ha•lâkh•âh′ according to their [oral tradition]? Because [Beit-Hi•leil′] were comforting and wretchedly-humble and we recite their oral-sayings and the oral-sayings of Beit-Sha•mai′, and not only that, [Beit-Hi•leil′ recited] the oral-sayings of Beit-Sha•mai′ before their [own] oral-sayings.

Thusly, we recite: [When] the former head and [former] majority is in the Sukah and his table is in the middle of the house, Beit-Sha•mai′ treats him contemptuously, but Beit-Hi•leil′ nurtures him to be kâ•sheir′'

![]()

(Translated so far)

|

|