|

|

3rd Century |

|

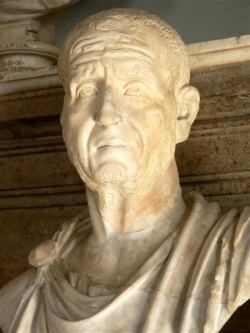

| Roman Emperor Severus (British Museum) |

To fan the flames of this crisis, the internal politics of the imperiate fell into chaos. After the death of Commodus, a military general, Lucius Septimius Severus (193-211 C.E.), seized power after two others had tried their hands at the imperiate in the same year and ruled as an absolute dictator. He decimated the economy by dramatically raising taxes, and he dramatically changed the character of the Senate by directly attacking senators. He replaced them with military men, so the Senate gradually began to look more like a military aristocracy. He established a rigid class system which slowly solidified to the point where social mobility was almost completely obviated. (wsu.edu)

"After the death of Septimius Severus in 211 C.E., the imperiate fell to the next in line in the dynasty, Alexander Severus. However, Septimius had set a precedent by seizing and retaining power using the provincial army under his control." (wsu.edu)

|

| Roman Emperor Caracalla (Altes Museum, Berlin) |

In 216 C.E., Caracalla made concessions to the Jews, including exempting them from taxes for the first time since Julius Caesar. On the other hand, successive Roman emperors increasingly persecuted the anti-Caesar âÌåÉéÄí Christians.

The surviving remnant Nᵊtzâr•imꞋ lived among—having been defended by—the

In this the Christians are correct: it was, indeed, the birthing Hellenist âÌåÉéÄí Christians, not the

"It was not an issue of belief, but of the system of religion. The Jews affirmed the same monotheist g-d claimed by the Christians, but they were tolerated, despite their rejection of the traditional g-ds, because they had a temple, they affirmed sacrifice. While the temple stood, they had sacrificed on behalf of the emperor. The one great difference on the part of Christians is that they did not even have basic religious observances in common with anyone in the empire.

"The Romans desired the pax

deorum. They feared that if they did not show honor to the g-ds unanimously through sacrifice and give them their rightful due in society, the g-ds would become angry and punish the Roman empire."Another issue was participation in ancient society in general. Since the Christians would not sacrifice to any divinity at all, they could not easily participate in civic government or the army, because if was impossible to avoid sacrifice to the g-ds during the routine rituals. Many Christians opted out of society, and also gave ten percent of their income to the church and its charitable programs. They had formed a shadow society in opposition to the Roman empire. They were thus characterized as "atheists" and "haters of humanity." (Prof. Christine M. Thomas, Religion and Western Civilization: Ancient, Univ. of California at Santa Barbara, religion.ucsb.edu).

After the death of Alexander Severus in 235, Rome saw a half century of "barracks emperors" who were all generals and seized power in the same way Septimius Severus had done. This half century, from 235 to 280 was the most calamitous period in Roman history. Internal politics had fallen into complete disarray, the economy had become a disaster, taxation in some cases approached near-confiscation levels, and foreigners made tremendous inroads in capturing Roman territory. The two last "barracks emperors," Claudius II Gothicus (268-270) and Aurelian (270-275), stemmed the tide slightly by pulling back troops from the frontier and hiring mercenary soldiers, but Roman government and stability would not be restored and reconstructed until the imperiate of Diocletian (284-305).

These were times of immense social crisis and fear. Even the statues of the emperors show this fear; while imperial statuary of Augustus and the early emperors (all the way up to Commodus) show heroic and powerful individuals, the statues of the emperors in the third century show worry and resignation and their faces are deeply lined with wrinkles and furrowed brows. They are amazing documents in Roman history, for the purpose of statuary is to present the ideology of the government; the Romans seemed so hopeless, that even the emperors were represented as weak and worried. (wsu.edu)

|

| Roman Emperor Philip the Arab (Hermitage Museum, Russia) |

From 244-249 C.E., Philip the Arab, of Syria, emerged from a distinguished equestrian family near Damascus to become Roman emperor. A Hellenist idolater himself, he was tolerant toward the emerging Hellenist Christian religion.

This λόγος holds that [Philip], being a Χριστιανοι, wished on the day of the last night-vigil of πάσχα, to share along with the multitude, the prayers at the church, but was not permitted to enter by him who was then presiding, until he confessed and numbered himself among those who were reckoned to be in sins and were occupying the place of penitence; for that otherwise, had he not done so, he would never have been received by [him who was then presiding] on account of the many charges made concerning him. And it is said that he obeyed readily, displaying by his actions how genuine and pious was his disposition towards the fear of

θεȋον[≡Ζεύς].

|

| Roman Emperor Decius (marble, Capitoline Museum, Italy) |

According to the historians in the TV documentary, Rise and Fall of an Empire, on the History Channel:

"By the middle of the 3rd century [C.E.], Rome ha[d] fallen into a full-blown crisis. Barbarians prey[ed] upon the weakening borderlands and civil war [broke] out across the empire… Desperate for answers, many Roman citizens look to their ancient [idolatrous] gods to deliver them from the perils war. But others find solace in a radical new religion—

Christianity.""

Christianity in the middle of the 3rd century [was] the most rapidly expanding religious movement in the Roman Empire. [There was] still not a lot ofChristians. I mean, let's not think in terms of more than a few hundred thousand. But it's a religion which is getting more visible." (David S. Potter, University of Michigan; Rome, Rise and Fall of an Empire, Episode 8, Wrath of thegods; History Channel)

Yet, these numbers and this visibility is exclusively in the gentile Roman citizenry, not in the Jewish community in which the

250x343.jpg) |

| Graeco-Egyptian |

Paraphrasing: In their Hellenist Roman tradition of syncretizing all known and newly discovered

gods, the emerging Hellenist Χριστιανοι Romans introduced a revolutionary new uniquely-Χριστιανοι innovation based on the foundations laid byΠαύλοςthe Apostate Hellenizer: syncretizing all of Hellenism's idolatrousgodsfrom their pantheon (polytheism) into a 3-in-1"Tri-une" god(Trinity) concept; into which they morphed all of the RomanTheology (idols) in:

a

Ζεύς-like image, based on Hellenist accounts by Greek-speaking Hellenist Jews, morphing the most powerful Hellenist idol,Ζεύς, into a divine "son of god" / "man-god" facet,a "

father" facet, plusa "

spirit" facet."In 249 C.E., while fighting on the northern frontier, General Gaius Messius Quintus Decius' soldiers proclaimed him Emperor, usurping Emperor Philip, who was in Rome. A resolute idolater having faith in the Roman

gods, " “[t]he most important thing to remember about Decius is that he is extremely traditional. He's very dedicated to a sort of almost mythical view of Roman values. And what that means, of course, is that things that can be perceived as un-Roman are looked at as dangerous by Decius”" (Michael Kulikowski, Univ. of Tennessee at Knoxville)."Decius [feared] Philip's Christian sympathies [would] anger the idolatrous

gods, worsening the crisis already enveloping the empire end-to-end… This [existential crisis of historic proportion for Rome was] no time to anger the[ir]gods." (Rise and Fall of an Empire, History Channel).

"Trajan [had] set the precedent that Christians were not to be sought out by Roman officials… a "don't ask, don't tell" policy…

"This principle was true until Decius (249-251 CE). In the context of a war against the Goths, Decius demanded sacrifice to the traditional g-ds of Rome by all Roman citizens. This now included most Christians, because all free inhabitants of the empire received citizenship under Caracalla in 212 CE. Christians were sought out for mandatory sacrifice to the g-ds, beginning with their leadership." (Prof. Christine M. Thomas, Religion and Western Civilization: Ancient, Univ. of California at Santa Barbara, religion.ucsb.edu).

Worshiping their "Triune" god exclusively, Christians refused to worship the idolatrous pantheon. That the situation of the Roman Empire continued to deteriorate "proved" (fallacy of post hoc ergo propter hoc) that the Χριστιανοι were, indeed, the breach of the pax deorum, the very root of the empire-wide suffering from the obvious punishment wrought by the displeasure of the traditional Roman pantheon.

This traditional Roman religious perception forced Rome (as perceived by both the Roman emperors and most of Roman citizenry) to turn back from the previous, positive, view of his predecessor, Philip, toward Χριστιανοι. Indeed, Χριστιανοι became perceived as the causa discidium from their traditional pantheon. Clearly, they reasoned, they must eradicate Χριστιανοι and, instead, return to the "traditional" Roman religion to assauge their pantheon's (perceived) displeasure with Rome.

The result was inevitable: a campaign to eradicate the pantheon-offending Χριστιανοι

(Notice that these were Χριστιανοι who were persecuted by Rome in the 2nd-4th centuries C.E., not,

"Compounding Rome's problems with external attacks from its numerous enemies across many of its borders, Decius' usurpation prompted an internal civil war as Emperor Philip rode out with his army to confront Emperor Decius to determine which would continue as emperor. In the ensuing battle of Verona, Decius easily dispatches Philip's army and kills Philip.

"However, Roman armies defeating Roman armies leaves Rome greatly weakened relative to its external enemies already encroaching its border in many breaches and Decius blames Rome's combination of crises on Rome's failure to please the Roman

gods, which he considers an absolute necessity to restore the security of the empire. "One of the things that Decius is very concerned with is the health and the correctness of Roman worship, of imperial worship. I think it's clearly the case that the crisis that the empire is facing, the very large number of civil wars and the very large number of foreign wars, makes a correct relationship with thegodsimportant." (Michael Kulikowski, Univ. of Tennessee at Knoxville; Rome, Rise and Fall of an Empire, Episode 8, Wrath of thegods; History Channel).

"Ready to overcome the crises they experienced in Philip's reign, the Senate welcomes the stringent idolatrous rule of Decius, complete with ritual sacrifice. The traditional religion of the Romans, we call it idolatry, involved worshiping and honoring and respecting many

godsandgoddesses. If the Romans didn't show their respect by sacrificing the animals, by really dealing in the blood and meat that literally brought life, then the Romans expected that thegodswould abandon them.” (Thomas R. Martin, College of The Holy Cross) For the empire at risk for Barbarian attacks on almost every border, it seems thegodshave already abandoned them" (Rome, Rise and Fall of an Empire, Episode 8, Wrath of thegods; History Channel).

"The third century in Roman history is often referred to as a period of crisis and the period when Decius comes to power is just as that crisis is really coming to a head. The situation on the frontiers is about as bad as it's ever been" (Noel Lenski, Univ. of Colorado; Rome, Rise and Fall of an Empire, Episode 8, Wrath of the

gods; History Channel).

Battles defending the borders, particularly on the northern borders, further depleting the Roman army—already so dangerously depleted by civil war as to tempt its enemies to the north to regularly challenge its borders.

"If something isn't done, the borders of the empire will collapse completely. To start, new idolatrous temples are commissioned by Emperor Decius in Rome, hoping to appease the angry

gods. Naming his son, Herennius, co-Emperor, Decius sets out to impose their traditional values on the entire empire. They will not tolerate Christianity or any other deviation from idolatrous devotion" (Rome, Rise and Fall of an Empire, Episode 8, Wrath of thegods; History Channel).

"What [Decius] did was insist that every single person make the sacrifice and obtain a certificate that they had done so. He was able to use the tax system, the tax rolls, to make sure that you could bring everybody in, and you had to make the sacrifice in front of witnesses" (David S. Potter, Univ. of Michigan; Rome, Rise and Fall of an Empire, Episode 8, Wrath of the

gods; History Channel).

Of course, most Christians refused, resulting in inevitable social exclusion and a widespread persecution of Christians.

250x185.jpg) |

| Temple to the Pantheon (Rome, built by Hadrian, 126 C.E.) |

In 250 C.E., Decius is betrayed by a Roman Senator who surrenders a principle northern city to the Goths, whom he pursues to engage in a pivotal and decisive climactic battle.

"In their camp outside [modern Razgrad, Bulgaria], Decius, his son, Herennius, and their legion's priest turn to the only force they know will guarantee victory—their beloved idolatrous

gods. “Decius knew that this was going to be the struggle of his life. So Decius did what he was supposed to do to win the favor of thegods. He sacrificed. And with the smoke rising to the heavens as far as the eye could see on and around the altars, then no one could doubt that Decius had done absolutely the maximum to try to win this titanic struggle.” (Thomas R. Martin, College of The Holy Cross; Rome, Rise and Fall of an Empire, Episode 8, Wrath of thegods; History Channel).

Fear of abandonment by their traditional idolatrous gods, not nonexistent religious power by a scattering of social outcast Christian clergy, prompted Church persecutor Decius to "[declare] that he would rather see a new pretender to the empire than a new bishop of Rome (Cyprian, Ep. lii)" ("Cornelius," Smith & Wace, i, 689).

The conflict, pressure, increasing Christian Hellenization (as contrasted with the waning idolatrous Pantheon) and antinomian (misojudaic) evolution continued until Constantine figured out how to take political advantage of it, ca. 313 C.E., and nationalized it at the Council on the northern Black Sea coast of Turkey (Nicea) in 325 C.E. (Salo Wittmayer Baron, A Social and Religious History of the Jews, 2nd ed., (New York: Columbia University Press and the Jewish Publication Society of America, 1952), II, 152).

As persecution of Christians failed to satisfy Rome's gods, demonstrated by their failure to restore Rome's fortunes—indeed, Rome's situation inexorably worsened, even the Roman citizenry began to lose faith in their idolatrous gods—and began to turn instead to Christianity. Christianity had hung on but was not a wildly popular religion in the Roman Empire until the third century.

In 251 C.E., despite having done everything Roman idolaters could possibly consider the maximum to appease their gods, the Goths overpowered Decius' army. Both Decius and his son were killed. Roman citizens could only conclude that their idolatrous gods were powerless to protect or help them.

Exacerbating this loss of faith in their idolatrous gods, also in 250 C.E., a plague—understood as a scourge of the gods—swept the empire, lasting until 266 C.E.; at its height killing thousands each day in Rome alone, including the last heir of Decius. Roman citizens at first blamed Christians for all of Rome's ills; yet, rapidly began to lose faith in their traditional idolatrous gods. Decius' persecutions of Christians hadn't won the favor of their idolatrous gods. Therefore, Roman idolaters concluded they must seek divine favor in other directions.

|

| Roman – soldiers' – |

In a world that seemed to be falling apart, the Roman population were beginning to lose faith in and abandon their idolatrous gods, seeking hope in the afterlife of Mithraism; a rare few, willing to suffer persecution and death from the Roman idolaters, opting for a revolutionary new faith and god—Christianity.

Other eastern religions, particularly Mithraism, which was derived from Persian Zoroastrianism, also promised an afterlife and a meaning to suffering and were more popular than the persecuted Christianity.

Χριστιανοι syncretized Mithraism, so that the two religions closely resembled each other:

They both involved the son of god taking a human form to experience human suffering;

the human life of this god involves a last supper

and an execution; and

both religions are eschatological and promise a final judgement

The difference, however, is that Mithraism is at least three centuries older than Christianity.

Χριστιανοι was deeply influenced by Mithraism. There developed several versions of Christian-Zoroastrian religions, such as Gnosticism and Manichaeism, and the interaction between these two religions affected the fledgling mainstream Christianity—such as the moving of the Judaic Sabbath day to Sunday (Mithra-day) and the celebration of the birth of the "son of god" on December 25 – neither of which have any precedent whatsoever in [the Judaic Mithraism, which had its day of worship on Sunday (Mithras was the god of the sun) and celebrated his birth in human form on December 25 (wsu.edu). By contrast, the date for the birth of historical ![]() 28 notes 28.1.1 & 28.1.2 with endnotes.

28 notes 28.1.1 & 28.1.2 with endnotes.

"The decline of Rome during this century seemed to point to an almost certain demise, and the promise of an afterlife or a mystical reunion with the One seemed to be the only thing to hope for. However, the last of the barracks emperors, a shrewd and practical man named Diocletian, radically reconstructed the Empire and set the stage for the Christian Roman Empire in the fourth century." (wsu.edu)

In the latter half of the 3rd century C.E., Rome's enemies were attacking all along the extensive borders of the enormous Roman Empire. The emperor could not be everywhere; indeed, by the time the emperor learned a problem was getting out of hand and marched to the battleground on foot, the situation had often spiraled out of control. Consequently, it was unavoidable for local generals to assume the emperor's role in such battles… as a result of which, the local armies increasingly proclaimed their local general a local emperor. This resulted in the breakdown of the Roman Empire into rival states—with rival armies. What had been a might empire increasingly became a chaos of often-conflicting states, declaring independence from Rome; sometimes fighting each other (Rome, Rise and Fall of an Empire, Episode 9, The Soldiers' Emperor; History Channel).

|

| Roman Emperor Aurelian (270–275 C.E.), bronze bust (Museo di Santa Giulia, Brescia) |

When Emperor Claudius died of the plague while fighting on the frontiers, Lucius Domitius Aurelianus (Aurelian), a skilled soldier and excellent and trusted general, was declared emperor by his soldiers (reigned 270–275 C.E.); the task of restoring the empire thereby falling upon him. While previous Roman Emperors had all worshipped Hellenist idolatrous pantheon of gods inherited from the Greeks, Emperor Aurelian reflected a growing trend in the Roman Empire toward monotheism—worshipping the One god of soldiers: (Roman Latin) Sol Invicta, the "UnConquered Sun"; Hellenist Greek Ἥλιος —the One deity for soldiers as the god of victory. (Rome, Ep. 9).

Suffering a route in the north in 271 C.E., enabling the Barbarians leaving the city of Rome itself exposed. Although Aurelian managed to intercept and massacre the Barbarians, saving Rome, the eastern provinces, which had deteriorated for a decade, declared independence from Rome and projected their power to the southwest—the breadbasket of the Roman Empire: the Nile Delta. When the eastern province cut off grain to the Roman Empire, the threat of famine instigated rebellion against Aurelian by the citizens in the city of Rome itself, which Aurelian crushed. (Rome, Ep. 9).

By 272 C.E., Aurelian was chasing the queen of the eastern province through Turkey and toward Iran, finally catching, and defeating her army, at the Euphrates River. However, Aurelian spared her life. "But before leaving [the eastern province], Aurelian visits a temple where he will pay tribute to one god alone, the god of soldiers, Sol Invicta, who has ensured his victory on foreign soil. “He clearly had in mind an alliance between him and the sun god that was responsible for his successes in [the eastern province]. He presented himself on his coins in terms of an association of the emperor to the god, Sol Invicta” (Florin Curta, Univ. of Florida).

" “Well, we're moving into this dimension of associating the emperor very closely with one particular divinity who clearly, given the success that he had already enjoyed, people might believe in” (Geoffrey Greatrex, Univ. of Ottawa) In the peace of the eastern temple, he sees that this is the one god to unite all of Rome" (Rome, Ep. 9).

" “He does seem to have been participating in a growing trend toward universalism both in religion and in Roman political control” (Noel Lenski, Univ. of Colorado). Offering his own blood as sacrifice, Aurelian promises his god a nation of worshippers" (Rome, Ep. 9).

In 273 C.E., Aurelian returned to Rome in triumph with vast treasures he had captured. However, Aurelian purposed to "use the riches taken from the east to establish the soldiers' god, Sol Invicta, as the single deity of the empire… “[He] actually put the new cult on a par with the official state religion in Rome…” (Florin Curta, Univ. of Florida)" (Rome, Ep. 9).

In 274 C.E., despite his return to Rome in triumph from the eastern province, the northwestern provinces (Europe) had declared their independence from Rome under yet another soldier-proclaimed local emperor. Aurelian determined to reintegrate what is now Europe and Britain and reunite the old Roman Empire under the one god, Sol Invicta. Defeating the insurgent army yet another civil war, he spared the life of its "emperor" as he had the queen of the eastern province. This time, returning to Rome in triumph again, having finally reunited the entire empire, Aurelian paraded the queen, the former "emperor" of the northern provinces and other captured important personages through the main streets of Rome" (Rome, Ep. 9).

"Grateful in his triumph, Aurelian consecrates the temple he has built for the god of soldiers, Sol Invicta, whose power and favor, he believes, have made him invincible. “Many scholars believe simply that this was trying to enforce conformity among the peoples of the empire for political purposes, and also for religious purposes, and those two things are not that easily separated in the mind of a Roman.” (Noel Lenski, Univ. of Colorado). Aurelian decrees this day, December 25th, will be celebrated each year as the birthday of Sol Invicta [though RibꞋi Yᵊho•shuꞋa was born on May 29th (B.C.E. 0007; NHM![]() 2.2.1)]. Later emperors, also seeking to unite Rome with religion, will adopt this date for the birth of

2.2.1)]. Later emperors, also seeking to unite Rome with religion, will adopt this date for the birth of Jesus Christ. Even now, over 1700 years later, this once idolatrous holiday is celebrated as Christmas around the world" (Rome, Ep. 9).

"Throughout the empire in the 3rd century, there's clearly a movement towards monotheism, towards different cults that believe in a single god and, sometimes, in a single redeeming god." (Michael Kulikowski, Univ. of Tennessee at Knoxville)" (Rome, Ep. 9).

In 275 C.E., insurgency broke out yet again in the eastern provinces. Enroute with his army to engage the eastern insurgents, Aurelian was assassinated, apparently by his soldiers—inexplicably, given his many military successes and achievements. As a result, the empire fragmented yet again (Rome, Ep. 9).

"One element that Diocletian brings in is a redefinition of the way frontiers were to be defended.” (Edward J. Watts, Indiana Univ., Rome, Ep. 10) Emperor Diocletian creates a mobile imperial army, always available to send reinforcements to the vulnerable frontier. One of his most capable imperial soldiers is Constantine, only 17 years old" (Rome, Ep. 10).

|

| Roman Emperor Diocletian (marble, Istanbul Museum of Archeology) |

"3rd century Rome is wracked by internal strife and Barbarian invasions. But by 295 [C.E.], a powerful new emperor has emerged as the empire's savior. His name is Diocletian" (Rome: Rise and Fall of an Empire; Ep. 10: Constantine the Great, History Channel).

"The Great Persecution was brought on by numerous individual incidents that played on Roman fears. In 295 CE, Christians in the army publicly refused to participate in sacrifice. In 302, a Christian interrupted a public sacrifice in progress at Antioch.

"Diocletian (284-305) began the Great Persecution (303-311), which was aimed specifically at wiping out the Christians. They were first declared as outlaws of the empire and stripped of their citizenship. This meant that they could take no government positions, could not defend themselves in court, and could become their employers' slaves. Their books were burned. In the second stage, Christians were rounded up and imprisoned. Finally, they were executed if they refused to sacrifice, because the prisons had become overcrowded. During this last stage, particular local governors carried out horrible pogroms. Christians in Egypt were tortured to death, in Syria the men were sent to the salt mines and the women to brothels, and in Asia Minor, entire Christian villages were executed.

|

| Roman Emperor Galerius (porphyry) |

"The persecution was finally halted by the emperor Galerius on his deathbed, as he lay dying of a horrible illness that he considered divine punishment: the Edict of Toleration (also known as the Edict of Gallienus), 311 CE, allowed Christianity for the first time to be a legal religious option in the empire."(Prof. Christine M. Thomas, Religion and Western Civilization: Ancient, Univ. of California at Santa Barbara, religion.ucsb.edu).

Another of Diocletian's reforms was to split the empire into four states, the western three each ruled by his appointed co-emperor, while he ruled overall from the eastern state. Recognizing the signs of greatness in Constantine, Diocletian keeps the potential rival close, in his court under tight control—away from Constantine's father, whom, in 293 C.E., Diocletian appointed co-emperor of the westernmost state (England and western Europe), lest Constantine become too powerful and threaten his rule.

|

|